Learning from mistakes:

First and foremost, it is performance deficits and not financing problems that bring companies to their knees.

What experiences from corporate restructuring and recommendations for timely countermeasures are there?

The insolvency rate in Germany has increased during the economic crisis. No wonder: markets are collapsing, banks are unwilling or unable to provide the necessary debt capital. On the one hand, there are companies – and not too few – that have been hit by the economic crisis and are nevertheless holding their own, while on the other hand, some companies have to go to insolvency court or be restructured even in more moderate recession phases, even in times of economic upswing. In our reorganization and restructuring projects, we are regularly confronted with the question of why a company is no longer sufficiently competitive, because this is where the levers are to be applied in a restructuring.

If you ask the companies themselves or follow the public discussion in the media, the same supposed causes that lead to liquidity crises dominate time and again, such as:

- Short-term collapse of markets

- Lack of “loyalty” of debt capital

- the international competition

- Currency fluctuations

- Export or import barriers.

To a large extent, however, this is just the last straw that broke the camel’s back. The real causes of the lack of competitiveness usually lie elsewhere. As Hauschildt1 pointed out a long time ago, the chain of causes and effects in companies can be traced back from a liquidity crisis to an earnings crisis and a strategy crisis to a performance crisis.

According to our experience from numerous restructuring and reorganization projects as well as expert analyses, it is ultimately performance-related deficits that erode the competitiveness of companies. Performance deficits can be profitable in good times, but cost lives in bad times. And this is the only way to ensure the long-term competitiveness of companies.

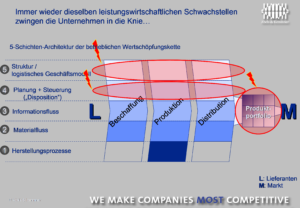

Our experience also shows that the problems are always to be found at the same points in the value chain! Figure 1 is a schematic representation of a value chain. If we take a closer look at a value chain, it becomes clear that it can be broken down into five layers. The lowest layer of value creation is the manufacturing process; what is done on a single production line or machine. The manufacturing processes are linked by material flows (layer 2). The material flows are triggered by information flows (layer 3). The information flows, in turn, are coordinated (“scheduled”) at the planning and control level (layer 4). The planning and control level in turn implements the logistics business model of the value chain (layer 5). The result of the value chain is a product portfolio that has to assert itself on the market.

The central problems that we repeatedly encounter can be found in the following three places:

- in the product portfolio

- in the planning and control of processes (layer 4), and

- in the logistics business model used (layer 5).

Let’s take a closer look at these three causes of illness below:

Sources of illness in companies

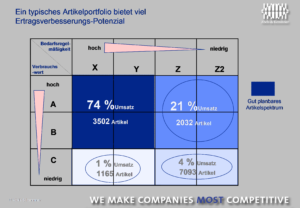

Figure 2 shows a typical product portfolio as found in many companies on the finished goods side. The individual articles were rated according to their sales significance (ABC) on the one hand and how regularly the market demands the articles (XYZ) on the other. It turns out that approx. 60-80% of sales are generated with 20-30% of the article numbers. At the other end of the portfolio, only 3-4% of sales are generated with 40-70% of items, which requires a considerable proportion of the total inventory.

At the bottom right of the product portfolio, with these CZ and CZ2 articles, hardly any money is earned. In process cost analyses, we repeatedly find that these items, even if the contribution margins still appear positive, burn money when costs are allocated precisely: High inventories and therefore capital commitment in relation to sales; high processing and administrative costs; high risk of scrapping.

Very few companies, and not just the economically weak ones, keep their product portfolio up to date. It is therefore not surprising that a typical method used to restructure and reorganize companies is “downsizing”: You get rid of a loss-making and expense-generating part of your product portfolio. At the same time, machines, inventories, infrastructure and personnel can be reduced disproportionately and the company returns to profitability. Such dramatic steps could be avoided with regular critical maintenance of the product portfolio. No staff cuts on the one hand and higher earnings on the other.

The second source of illness is the fourth layer, the planning and control of the value chain. Despite 50 years of experience in PPS and ERP systems, many companies still do not have a continuous planning chain from sales planning to production control; there are often manual steps in between in the form of Excel planning. Instead of using the automatic planning mechanisms of the ERP system, work is done by hand: the ERP system only serves as a golden typewriter.

What was still possible 30 years ago with few and simple products and production processes using a wall-mounted planning board can no longer be maintained today. The importance of efficient scheduling and production control is systematically underestimated in most companies. 153 billion in excess inventories2 during the economic boom in Germany is just one indicator of the inefficiency of replenishment processes. Without efficient and automated planning and scheduling processes in key areas, there can be no sustainable profitability! In many restructuring projects, and not only there, the liquidity required for the implementation of measures can be obtained from the reduction of inventories.

A company not only has a corporate business model, but also a logistics business model; the two business models often do not work in sync, which brings us to the third source of the problem: While the corporate business model is constantly adapted to market requirements, the logistics business model often remains unchanged (see Figure 3).

A high number of variants that are created far too early at the start of the first production steps, excessive delivery readiness for items that are rarely in demand, incorrect logistical decoupling points or a lack of market-synchronized production are just a few examples of a lack of coordination between the logistics business model and the corporate business model.

However, it is not enough to identify these problem areas when it is actually too late. Why are these problems in many companies not rectified in good time and in good times? In our experience, there are four main reasons for this:

Internal target systems block the right solution

Internal target systems are very popular today; in small and medium-sized businesses as well as in large-scale industry. What better way to motivate all managers to increase the company’s earnings than to break down the goal of increasing earnings into sub-goals for the various areas of the company? Purchasing should reduce the purchasing volume in relation to sales. Production is intended to increase plant capacity utilization. Sales should increase turnover and logistics should reduce inventory costs.

Each individual target sounds nice, but as the individual targets are not independent of each other, improved targets in one area are often at the expense of other areas. In this way, area egoisms are strengthened and everyone is interested in their own optimum, but no one is interested in the overall optimum. As a result, it is precisely those improvement measures that have an impact across the value chain and can contribute most to increasing a company’s competitiveness that fall by the wayside: the adaptation of the logistics business model and the planning of the value chain. For the same reasons, product portfolios proliferate like weeds in many companies.

Two approaches help to solve this problem: On the one hand, consistent target systems are needed in which causation and responsibility are brought together and in which managers are measured more by their contribution to the company’s overall performance. On the other hand, the functions within the company that bear cross-sectional responsibility in the value chain, such as logistics and supply chain management, must be strengthened. The traditional specialist departments are thus slipping more into the position of service providers.

The company’s own expertise is overestimated

In crisis situations in the past, many companies simply set the wrong priorities for their further development. In some cases, there is a lack of expertise to correctly identify priorities. Most managers only know a few design variants for certain tasks in their area of responsibility, with which they have gained experience in their professional life. They fall back on these again and again, at best modifying them slightly. They are subsequently unable to assess the strengths and weaknesses of these solutions, especially if the operational conditions on the market change. Ultimately, they usually lack sophisticated tools for designing and interpreting the right solutions.

As companies’ value chains are becoming ever more complicated and competitive, the days when you could build your own hut are coming to an end. Companies must reduce their conceptual depth of added value and rely more on external experts instead of “tinkering” themselves. It is better to buy in “best practice” instead of developing “medium practice” yourself over a long period of time.

Slow decisions due to weak leadership

Even if a consensus cannot be reached, decisions must be made. However, leadership in the traditional sense is lacking in many companies: If there is no consensus on a problem or a solution in the management circle, discussions continue at best, but no decisions are made, nor are experts called in to summarize the problem and develop a solution. If employees resist a change, it is delayed instead of convincing them or making it clear to them that there is no alternative.

In many companies, it takes too long to go from suffering, to consensus on the existing problem and forming an opinion on the right solution, to the hope of improvement and the introduction of measures. In restructuring cases, we almost always come across individuals in the company’s management circle who are aware of the problems but were unable or unwilling to push through decisions. In my experience, the causes of a lack of leadership strength are not only to do with the individual personality structure, but also stem from a lack of qualifications for assessing problems and finding solutions, and are reinforced by the unsuitable target systems already mentioned.

Overworking employees and managers

Many necessary decisions in the company are also made too slowly and many concepts are not developed carefully enough because managers and employees in many companies are notoriously overworked. On the one hand, savings are being made on every head, on the other hand, work is still too cumbersome and ultimately too much effort is being put into product segments in which too little revenue is being generated. This brings us back to the product portfolio and closes the circle, so to speak.

There is nothing good unless you do it. It is very rare for market requirements and demands on the value chain to change so quickly that a company is unable to keep up. The prerequisite for this is that there is no backlog of solutions and that a company keeps its value creation engine well maintained and up to date. Those who only react during a crisis have neither the time nor the money to become sustainably competitive and can only improvise. If he doesn’t pay with his downfall, then at least with his silverware.

1 Hauschildt, Jürgen: Crisis diagnosis through balance sheet analysis, Cologne 2000

2 Abels & Kemmner: Overstock analysis Germany 2009. Quelle: https://www.ak-online.de/2009-03/pm2009-1