Too much “on the high side”? Security holdings do not earn interest

In the last issue, we presented the first eight rules for efficient scheduling and explained why delivery readiness should be at the beginning of scheduling planning. Below we explain how to determine the ideal level of your safety stocks, when they are useful – and when they are not. You will also learn what the architecture of the value chain has to do with basic and safety stocks. So here are your next steps into a new world of scheduling:

According to the first eight steps for first-class scheduling, you have now clarified your logistical positioning, defined your delivery readiness and initiated measures to measure it. You have made forecasts and replenishment times much more reliable and have at least planned systematic batch size management. This means you have already done a lot to train the heart of your company, the scheduling department, for the daily production marathon. But it is not enough to be able to run the marathon to the end. If you want to be on the winner’s podium, you need even more:

Basic principle 9: Manually set safety stocks are usually incorrect.

Disposition is very often about statistics, and it also plays a major role in determining safety stocks. Unfortunately, humans do not have a sense for statistical correlations. This can be seen very clearly in an example outside of logistics: every year, an average of five people worldwide die from shark attacks, while 150 people are killed by coconuts on beaches. Nevertheless, the beaches in the tropics are full of sunbathing tourists. However, if a shark is reported to have been seen within a few tens of nautical miles of a beach, nobody goes into the water.

Since you cannot rely on a reliable sense of statistical correlations, it is extremely clumsy to define safety stocks manually. A supposedly sharp look at past inventory trends, dregs analyses or the acute experience of a stock-out are also bad guides for determining the size of safety stocks. unfortunately, most ERP systems only help you to a limited extent in the statistical determination of safety stocks:

If safety stocks can be determined automatically at all, they are usually based on inadequate statistical concepts and relate only to delivery safety stocks and not to procurement safety stocks. The fact that the ERP system cannot do something is no excuse when it comes to achieving best practice levels. There are sufficient tools and mechanisms to correctly determine safety stocks. Therefore:

Best practice module 9: Safety stocks on the stock receipt and issue side as well as in production must be automatically calculated, set and built up on the basis of reliable statistical mechanisms in order to achieve best-practice planning.

Correctly determining the amount of safety stocks is critical. But it can be even more problematic to create them in the first place. The reason for this is the next basic principle:

Basic principle 10: If safety stocks are needed, it is too late to build them up.

Safety stocks are unpopular, as they supposedly only cost money but bring in nothing. Many companies are therefore reluctant to actually build up safety stocks. On the other hand, they take every short period during which they do not have to touch the safety stocks as an opportunity to reduce them again. But when there really is a fire – and there really will be a fire! – then it is too late to build up the stocks.

In the best-case scenario, the set-up takes time and the market exercises patience. Often, however, the supplier or the company’s own production facilities are no longer able to deliver the required quantities. Safety stocks can usually only be built up at times when they are not yet needed. That is why we should hold fast:

Best practice module 10: Determine the required safety stocks regularly and build them up in good time, i.e. before they are needed.

Inventories are an organizational lubricant in the logistical gears. Consequently, inventories are also very well suited for evaluating logistical performance, as the following applies:

Basic principle 11: Basic stocks result from the architecture of the value chain, safety stocks from its process stability.

Let’s imagine that the entire value chain functions without disruptions: no irregular replenishment times, 100% adherence to production deadlines, no quality problems, customers who collect their ordered goods on time, and so on. Would such a process chain be inventory-free? If it is to work as cost-effectively as possible, of course not, as we know!

It would hardly make economic sense, for example, to procure each screw from China individually and deliver them in sync with demand. Stocks that are required for the operation of such an ideal value chain are referred to as basic stocks. Working without stock, i.e. without basic stocks in the value chain, is a theoretically conceivable solution, but not an economically viable one. At some point in every supply chain, you reach the point where further reducing stock levels elsewhere in the value chain causes more costs than the reduction in stock.

In the following, we refer to this total cost minimum as the “optimum operating point”. Clever changes to the architecture of the value chain make it possible to work with lower base stocks at the same cost, i.e. to shift the optimum operating point towards lower stocks: By creating variants late in the process, as close to the customer or market as possible, you will manage with lower base stocks. The same applies to a lower number of inventory levels, a very early logistical decoupling point or highly flexible production. Not every measure is technically feasible and almost every one also incurs costs. The optimum operating point will therefore probably never be zero basic stock.

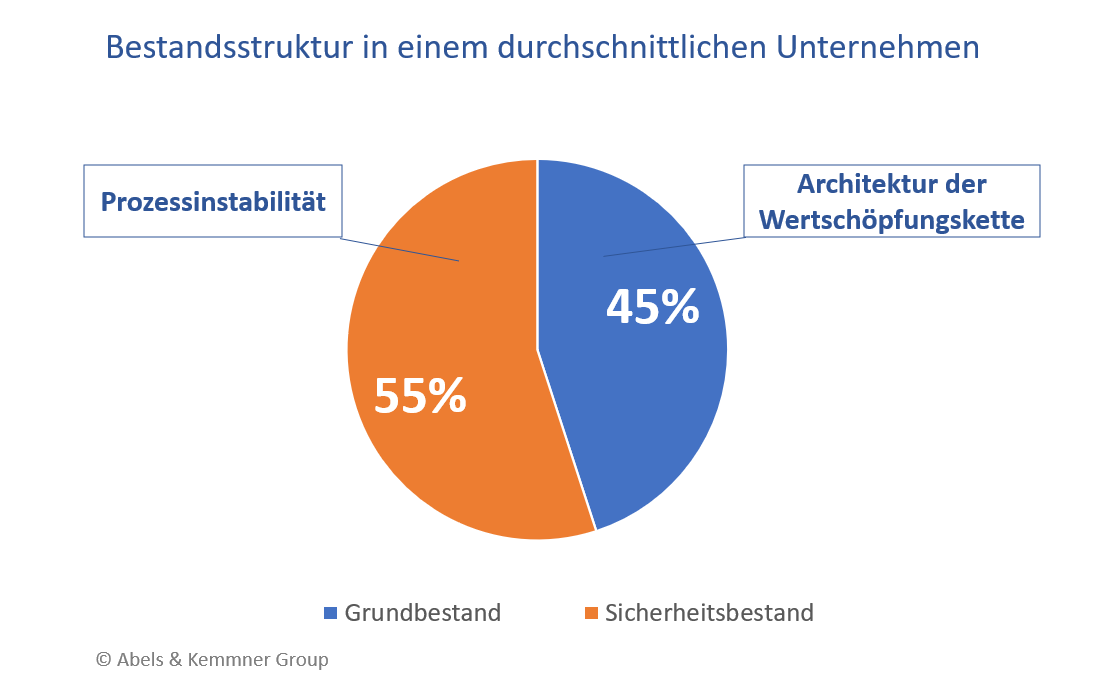

Even if we were able to realize an economic value chain with “zero” basic stock, we would not necessarily manage without stock in the real world. In the real world, an infinite number of disruptive factors impact the value chain, above all fluctuating demand, unreliable delivery times in procurement and production and quality problems. The safety stocks already discussed in detail are required to cushion all these disruptions. Safety stocks are no small matter! In an average company, safety stocks account for 55% of total stocks compared to 45% of basic stocks!

Here too, of course, it is possible to reduce the required safety stocks by eliminating uncertainties and thus shift the optimum operating point towards lower stocks.

Basic and safety stocks are therefore a good indicator of where in the value chain further improvement measures need to be considered. Required basic stocks indicate starting points for improving the architecture of the value chain, while the necessary safety stocks point to areas where process instabilities need to be reduced. While everyone likes to focus on logistical measures to reduce base stocks, often without being aware of the difference between base stocks and total stocks, logistical process reliability is often forgotten. Another best-practice building block is therefore to be noted:

Best practice module 11: Unreliability in the logistics chain that cannot, should not or must not be eliminated must be intercepted by safety stocks.

Once the central logistical parameters discussed have been set correctly, the task is to plan and control them sensibly and efficiently.

This might also interest you: