Part 3 of the best practice rules for efficient scheduling

In the first two parts of this best practice article, you learned which eleven building blocks and rules you can use to define delivery readiness and safety stocks. You now know that you need to build up safety stocks before you need them and therefore need to determine them regularly. The architecture of your value chain now determines your basic requirements and you can derive your safety stock from the process stability. now it is a matter of making your planning fit enough to take off into new worlds! Read on to find out when pull and when push control makes sense, why dispatchers’ gut feelings are unfortunately unreliable and why sets of rules are essential for efficient scheduling. The last steps into a new world of scheduling:

Classic push controls, such as planned MRP or MRP II, are no longer “cool”, but rather “out”. Everything strives for lean production and “pull control”: reorder point control and above all Kanban (shuttle cards) are “in”. Both are very old methods that were already in use before the age of computers, pendulum maps at least as far back as the Middle Ages. There are many reasons for the renaissance of pull control, but it is often overlooked that push control was once developed to overcome certain disadvantages of reorder point control and that there is practically no such thing as pure pull control.

Pull control in its classic form is primarily suitable for uniform average requirements of recurring items with a fluctuation variance of up to 1. Pull mechanisms can be deformed so that they also work for one-off and small batch production, but then they no longer offer any advantage over push control. 100 years ago, reorder point control meant that a mark was placed in the warehouse at the stock level at which new material had to be reordered. Reorder point control today means that the stock level in the warehouse is tracked via the book inventory and reordering is triggered when the stock level falls below the book inventory.

In order to save booking effort, retrograde booking is popular today. Material is only debited from a warehouse when the production order requiring the material has been processed and confirmed. The old material is therefore only debited when the new material is added to the warehouse. As a result, the book inventories always lag a little behind the physical inventories: not a happy starting point for electronic reorder point control. Retrograde booking and reorder point control do not go well together.

Kanban control is also nothing more than a reorder point control system, but one that is based on physical stock. In contrast to reorder point control, the Kanban system monitors the increasing empty containers and not the decreasing stock in the warehouse in order to trigger replenishment. A manual Kanban system, for example, has no problems with retrograde debiting of book inventories. Many companies encounter problems in the Kanban system when it comes to calculating or recalculating the required number of cards or containers in the control cycle.

While reorder points are adjusted regularly, Kanban stocks are left constant for as long as possible. And while at least qualified planners know that a reorder point is made up of basic requirements and safety stock, the safety stock in the Kanban control cycle is often forgotten or set “by feel”. When designing a Kanban control cycle, many consultants are no longer even aware that the required degree of readiness for delivery must be included in the calculation, and traditional multi-level reorder point and Kanban control systems cannot cope with seasonal demand and trends. In such cases, it is not enough to regularly re-dimension the control loops and reporting systems.

Instead, special mechanisms such as parabellum control or reorder point control with MRP are required in order to adjust to increasing or decreasing requirements at lower MRP levels in good time and thus be able to handle the increase or decrease in requirements at the higher MRP level. If you don’t know how to deal with this because you don’t have the knowledge or functionalities in the ERP system, then it’s better to fall back on plan-controlled replenishment in such cases. several items that are ordered from the same supplier or procured with the same transport carrier must be planned together in order to achieve full containers, exceed minimum order values or adhere to order budgets, for example. the examples could be continued indefinitely, but it should already be clear:

Best practice module 12: Efficient replenishment uses a broad repertoire of replenishment methods depending on various boundary conditions and article characteristics and never lumps all articles together in terms of replenishment.

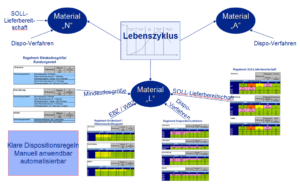

However, the differentiated application of different scheduling procedures for different articles only shows the tip of the iceberg of efficient and process-stable scheduling, because there is no static relationship between articles and all their master data and parameters that has to be set once. Rather:

Basic principle 13: The planning, forecasting and scheduling procedures and master data of an item must be continuously adapted to changing requirements.

Even if it rarely happens in practice: There is a consensus that central logistical master data, e.g. batch sizes or replenishment times, must be regularly adapted to changing situations. The fact that the ongoing readjustment also applies to the other logistical parameters of each item is much less well known. An item that previously had to contend with strong fluctuations in demand may now run quite evenly.

Whereas in the past only a few customers demanded this item or the end product in which this item is incorporated, today it may be ordered by a large number of customers. In the event of such changes, a different disposition procedure may have to be set for the article. The ongoing updating of scheduling procedures, parameters and master data is not an exception, but a regular requirement that is often ignored in practice.

Which rules should be applied to which items and how does not depend on the logistically relevant properties of the items. Necessary, but by no means sufficient criteria to be considered in any case are the importance of an item for sales (ABC), the fluctuations in demand for an item (XYZ), the number of demand generators behind an item (STU) or the life cycle of an item (ELA).

The realization that articles need to be maintained is surprisingly slow to lead to corresponding activities in many companies. Dispatchers are often instructed to check and adjust the master data of their articles more regularly. So everyone does what they think is right – one person does this, the other that! A strange generosity that the same companies do not grant to their production. For the production processes, it is clearly defined which technical procedures, which process parameters and in which work steps the parts are to be processed. Anything else would hardly lead to reproducible, reliable production processes. In order to achieve an efficient best-practice disposition, the following naturally applies:

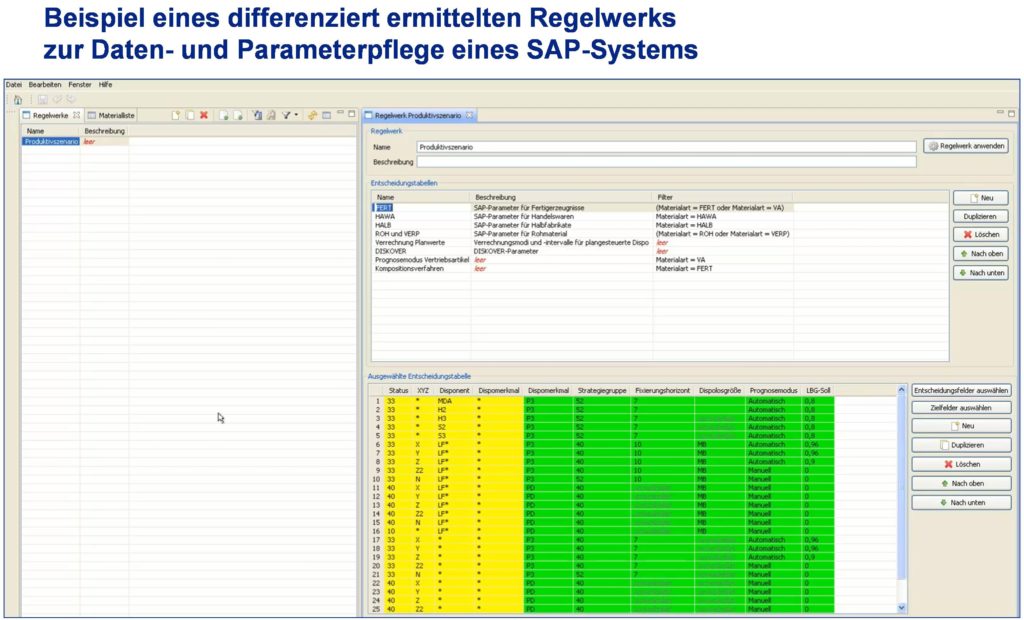

Best practice module 13: Which parameters, planning, forecasting and scheduling procedures are set under which boundary conditions must be uniformly defined in clear business rules and not left to the individual opinions of individual schedulers. The parameter settings are defined depending on logistically relevant article properties.

How do you arrive at uniform business rules? Please don’t drum up the entire scheduling department and discuss the correct hiring rules together! Another basic principle must be observed here:

Basic principle 14: Dispatchers’ gut feeling is one of the biggest inventory drivers in the company.

The technical term “behavioral economics” is used in economics to describe numerous papers on the influence of gut feeling and supposed experience on business decisions. It would go too far to discuss the details here. However, the conclusion of the studies can be reduced to a simple denominator: Neither professional nor private investors beat the market. Successes achieved through “good”, or rather “lucky” decisions in one place are undone elsewhere.

The reasons for this are the same as for shares and other securities and lead to planners overestimating their own experience and gut feeling. Furthermore, dispositive decisions and thus dispositive rules and regulations have a greater impact on the entire value chain than any human being, no matter how experienced and intelligent, is able to oversee.

Manual rules or rules based on the supposed experience of dispatchers or consultants alone may lead to reproducible dispatching results, but they also cement the “underperformance” of the entire value chain. Bad disposition cast in clear rules still remains bad disposition. The following therefore applies to top companies:

Best practice module 14: The right scheduling business rules for high-end scheduling are optimized for maximum logistical performance and minimum value chain costs using simulation, rather than based on experience and gut feeling.

If you have defined clear rules and used a differentiated simulation to set the rules in such a way that you achieve the required logistical positioning at the lowest possible cost, then you have taken a great leap forward. Don’t make the mistake of regularly updating the item settings manually according to the rules, because:

Basic principle 15: Data maintenance is too time-consuming to be carried out manually.

In order to keep the data quality up to date, the parameter settings must be maintained monthly in accordance with the rules and regulations. This cannot be done manually for two reasons:

Firstly, the mere monthly entry of changed master data on an item-specific basis in accordance with the rules and regulations would be too labor-intensive and time-consuming and therefore impossible to manage manually. The second reason is the classification of articles: Rules and regulations are largely based on the classification properties of articles. For example, if an article belongs to the class of incoming articles, it is handled differently to an article that belongs to the class of outgoing articles. The classification of an article is sometimes based on extensive calculations. This is already clear from the “standard classifications “ABC” and “XYZ”. These calculations must be updated with each maintenance run, which cannot be done manually.

Software systems that can process such sets of rules suggest the required setting changes per item to the user. The proposals can still be revised by the user and must be approved for upload to the ERP system. This semi-automatic approach is the only way to ensure that the “mass” data maintenance that is actually required is actually carried out regularly. Therefore:

Best practice module 15: Rules and regulations must be applied semi-automatically to the entire range of articles on a monthly basis. To do this, the items must be reclassified or reclassified in advance according to their logistical properties.

Slowly you have fought your way through the undergrowth and cultivated the forest of disposition again. Reliable scheduling parameters were an important step in this direction, but are still valid:

Basic principle 16: An ERP system with yesterday’s information cannot make decisions for tomorrow.

Unfortunately, it is not enough to have defined the correct logistics sizes for specific items and to have coordinated scheduling procedures. If the ERP system lacks information about the current status of production, procurement and delivery, it will be of little help to you.

How is the ERP system supposed to make correct stock decisions if the stock information in the system is incorrect or available far too late? How can it schedule production orders correctly if the required input material is not delivered on time by the supplier? What if the procurement department does not regularly check this important and critical date and at least enter changes to dates in the ERP system as soon as it becomes aware of them?

For production orders with longer throughput times through production, the completion of individual work processes may have to be reported back so that the ERP system has a sufficiently up-to-date overview of the capacity loads on the individual production systems.

We have already discussed the serious impact of incorrect delivery times on the support efficiency of the ERP system elsewhere, and these few examples already show that maintaining the scheduling parameters alone is not enough to build a useful ERP system. Just as a car is useless without gasoline, an ERP system is useless without data injection in the form of current transaction data. The transaction data includes not only stock values, but also delivery, replenishment and throughput times, production progress and delivery status.

A company whose ERP system contains up-to-date and accurate data is on the verge of bankruptcy – it is too time-consuming and cost-intensive to keep all values up to date. Even in residents’ registration offices, which operate “citizen data management” with large departments, the data quality is less than 100%! The art of data quality management in the ERP system consists of knowing under which boundary conditions and at which point in the planning steps what accuracy is required and how strongly deviations in the up-to-dateness, quality and completeness of the data affect the planning quality of the ERP system:

Best practice module 16: Status information on procurement, production processes and capacity loads must be reported back to the ERP system in a sufficiently timely, complete and error-free manner so that the system can make reliable decisions. Regular audits must check whether feedback is sufficiently up-to-date, complete and error-free.

A well-maintained and correctly configured ERP system lays the foundation for moving forward on the best-practice path and working to eliminate another shortcoming in many companies:

Basic principle 17: In many companies, ERP systems are only used as expensive typewriters.

Imagine that everyone in production does what they want. There are work schedules, but you don’t necessarily have to stick to them if you know better. Instead of working according to clear guidelines and quality criteria, everyone does it the way they think is right and of sufficient quality. You think that doesn’t exist in modern companies? Certainly not in production, but in the handling of planning and scheduling processes. Worse still, the proportion of companies operating in this way is actually increasing!

Paradoxically, the improved user-friendliness and transparency of many ERP systems and the development of so-called cockpits, which present all the information required for a user decision in a clear and often graphically supported manner, have played a major role in this. The supposed transparency of information often acts as a gut feeling booster for the user and the deceptive feeling of false security leads to wrong decisions being made. This regularly recognizable effect does not speak against the improved user-friendliness of such aids. However, it shows that discipline is required in the application. Even if this is often not demanded because people are not aware of its necessity.

You can only achieve process-stable, reproducible planning and scheduling processes that are independent of fluctuating human experience and overestimation if you automate your planning and scheduling processes to a greater extent and humans only intervene for two reasons: Firstly, to correct wrong decisions made by the system as a result of the system not being aware of certain decision-relevant information. Secondly, to readjust the “tuning” of the system (the rules) if the system has made a “wrong” decision that it could have made correctly if the parameters had been set correctly.

Of course, these principles cannot be used to achieve the precision and reproducibility of a machine tool’s CNC program. However, the aim must be that 80% of the system proposals can be “waved through”. This can also be achieved if the best practice rules discussed above are consistently observed. For the remaining 20% of system proposals to be corrected – and only there – the “cockpit effect” tends to have a positive impact. However, there is always the danger of replacing wrong suggestions with wrong gut feelings.

A best-of-class replenishment system must therefore also provide support for special replenishment cases, such as discontinuation and run-in planning, spare parts management or the joint replenishment of several items.

Best practice module 17: Planning and scheduling processes must be automated to be as process-stable as possible and therefore strongly rule-based, and system-based support must also be available for special scheduling cases.

The ERP system is set up correctly, data is reported back cleanly, scheduling processes run automatically as far as possible – what else stands in the way of success? In many companies, the first and foremost problem is the poor forecast data on which scheduling must be based. The sales and demand forecast is an essential prerequisite for the success of the disposition, as the following applies:

Basic principle 18: Vague assumptions about future needs are deadly poison for any disposition.

Planning can rarely afford to be based on specific customer requirements. For the majority of articles, you will have to rely on assumptions about the future development of demand. Steering effectively with poor demand forecasting is like trying to sail a powerful ship successfully without knowing which way the wind is blowing.we have already discussed the best practice rules required for powerful sales and demand forecasting elsewhere (see Best Practice Rules for Sales Forecasting). We just want to make a note here:

Best practice module 18: Best-practice scheduling is based on a best-practice forecast and an efficient plan distribution calculation.

If you fulfill the best-practice criteria described, then your scheduling really is working at a world-class level. With regard to production control, however, there are still some lights to be turned on in order to regulate production according to best-in-class criteria.

A new world of scheduling

Companies that have implemented the best-practice modules described live in a new world of scheduling: scheduling decisions are made faster and more reliably and are significantly less dependent on the experience and gut feeling of the individual user. Staff turnover in scheduling is less critical. The ERP system finally does what it is supposed to do: It handles the mass of routine tasks and leaves the dispatchers the time to deal with the really tricky issues.

The planning and control process becomes more transparent and efficient, reducing stress, hectic and frictional losses between company divisions. However, the new world not only offers a calmer working environment, but also hard-hitting business advantages: A more stable supply readiness on the market leads to more satisfied customers and lays the foundation for increased sales and higher market shares. It also means that less reorganization is required in production, which has a positive effect on production costs and reduces the overall costs of the value chain.

High potential

Experience from numerous projects shows us that an inventory reduction of 15 % to 25 %, combined with a more stable and better readiness to deliver, can be achieved if the rules and regulations have been optimized in a sufficiently differentiated manner. In addition, the further automation of scheduling processes reduces the requiredpersonnel expenditure by 25 % to 45 %.a new world that can be reached without risks and offers its benefits to anyone who consistently sets out on the path!

You might also be interested in: