Part 1: How to recognize hidden cost traps in your product portfolio

Many, if not practically all, companies are constantly struggling with the consequences of the “CZ explosion”: the diversity of variants in their product portfolios is blowing up in their faces, inventories are rising despite declining delivery readiness, and margins are eroding. In most companies, variant diversity is still seen as the solution to all sales problems. In the following, we will take a closer look at what successful companies are doing in terms of logistics and supply chain management to get a handle on variant diversity.

Dealing with the product portfolio is often seen as the domain of product management, sales and marketing. Without wishing to interfere with the responsibilities of these areas, there are good arguments for not ignoring the voice of logistics and supply chain management when it comes to maintaining the product portfolio. This is because supply chain management often has one of the most objective voices in the chorus of emotions that sing about product portfolio management.

It sounds terribly boring at first, but it’s terribly true:

Basic principle 1: A product portfolio costs money – and so does every expansion of it.

Every new product incurs costs in development, production and especially in logistics. Logistics performance is a service feature of every product on the market. This applies to products that have already been launched as well as to new ones. We naturally expect the online mail order company, for example, to have the ordered products in stock. What’s more, we expect them to be delivered by the parcel service the next day! However, if we are frequently informed by a retailer that the products we ordered are not available, we switch to the competition – no matter what great corporate image the marketing and advertising strategists have created.

Such requirements have long since ceased to apply only in the business-to-consumer sector. In the business-to-business sector, too, ever shorter delivery times and ever greater readiness to deliver are required. Logistically, the demands of the market mean two things above all: stocks and capacities. If finished products do not have to be kept in stock anyway, at least semi-finished products must be kept in stock, sometimes at high value-added stages, so that they can be completed into finished products at short notice. The former requires high inventories, the latter flexibility in production and transportation capacities and, in any case, both cause costs!

The price of a product must also take into account the total logistical costs associated with a particular value proposition. For new products, these logistical costs are usually too high to really be included in the price. In preliminary costing, overhead rates are often applied to the direct costs. These surcharge rates result from corresponding cost allocations from the operating accounts and therefore represent an average value approach. If each individual part carries this percentage surcharge, then these costs are covered. Although this is correct, it does not take into account the fact that the actual distribution of expenses and thus cost causation is not proportional to the direct costs.

New and exotic products cause high logistical standby costs in the form of basic requirements and, above all, safety stocks. Both groups often suffer from strongly fluctuating demand and therefore require high safety stocks in order to be able to deliver. Offering new products without being able to deliver them may make the product sexy in some sectors, but in others it makes it a flop.

Nobody in a company wants a new product to vegetate in exotic status forever. Rather, the hope is that demand for the product will increase and become more regular, so that future logistics costs will fall, and then sales, scheduling and – if available – product management check far too rarely whether these expectations have actually materialized. If the hopes for product success are not fulfilled, the sales department in particular then likes to point to the product range constraints: this makes it necessary to keep a product in the range that does not cover costs in order not to jeopardize the sale of other, more lucrative items by losing good customers. And so the number of exotics in the product portfolio grows until the critical mass is exceeded and the “CZ explosion”, which we will take a closer look at later, takes its course!

At this point, we must note best practice building block no. 1: Every new product requires a “Residual Lifecycle Cost” analysis, which must be updated every three months.

The main cost packages that should be regularly, if not continuously, monitored for new products include logistical standby costs, current disposal costs and the development of real contribution margins. In our experience, it makes no sense to focus on the “total lifecycle cost” at this stage. “Sunk costs, i.e. costs incurred in the past, are no longer relevant for future decisions. Only the costs incurred in the future play a role here.

The decisive factor in logistics standby costs is the warehousing costs for the necessary basic requirements and safety stocks across the entire supply chain. It is not only inventories at finished goods and component level that play a role here, but also inventories that are held by suppliers but financed by the customer.

If a product is no longer offered on the market, residual quantities of raw materials, materials, semi-finished products and finished goods occasionally remain, which can only be sold at reduced prices or even scrapped or disposed of as hazardous waste. The balance of these costs represents the disposal costs. Suppliers generally demand acceptance obligations for specific raw materials, drawing parts and product-specific assemblies if these parts are not accepted by the customer within a defined period of time. All of this also counts as disposal costs.

Ultimately, the development of the contribution margin must be continuously monitored for each new product. Negative contribution margins may be temporarily unavoidable from a market strategy perspective, but they must be eliminated quickly.

Looking at contribution margins alone is useless: they rarely reflect the logistical standby costs realistically, nor do they take future disposal costs into account. Articles with negative contribution margins are definitely “red” – but articles with positive contribution margins are not definitely in the “black”.

While product management, sales and marketing think in terms of product groups, product group hierarchies, product groups and market segments, these structures are not sufficiently differentiated from a logistics perspective. Structuring criteria for the product portfolio must go deeper and evaluate the logistically relevant characteristics of a product portfolio:

Basic principle 2: A product portfolio only becomes transparent in logistical terms through structuring and classification.

The importance of a product from a logistics perspective is expressed above all in its warehouse throughput. Warehouse throughput is the quantity of a material leaving the warehouse multiplied by its cost price. At the finished goods level, these are typically the sales quantities, valued at cost of sales. Based on the warehouse throughput, the articles can be differentiated according to the classic ABC approach – e.g. 80/15/5. In addition, ABC analyses according to stock, cover amount or turnover can provide important information.

The fluctuations in demand for a product that the value chain has to cope with are classically described in terms of X, Y and Z classes. X-items enjoy a rather regular and consistent demand, demand for Y-items already fluctuates significantly and demand for Z-items flutters. For various statistical and strategic reasons, we also differentiate between Z2 articles, the demand for which, in practical terms, represents the “disaster that has become demand”.

The ABC/XYZ classification of articles and materials is now part of the minimum standard in logistics, but even this is still not very common in many companies. Moreover, these two criteria are not enough to evaluate a product portfolio from a logistics perspective. Rather, the life cycle of an item and the number of consumers must also be taken into account.

As part of its life cycle, an article passes through the incoming (E), live (L) and outgoing (A) stages. The number of demand generators behind the quantity requirement of this article is also of great importance for the right logistics strategy and can be classified according to STU. S articles have one or two, T articles have a small number and U articles have a large number of demand generators. At finished goods level, these are the direct customers; at component level, the higher-level materials that trigger dependent requirements.

Best practice building block 2 says: Structure your product portfolio according to at least the four most important dimensions ABC, XYZ, ELA and STU.

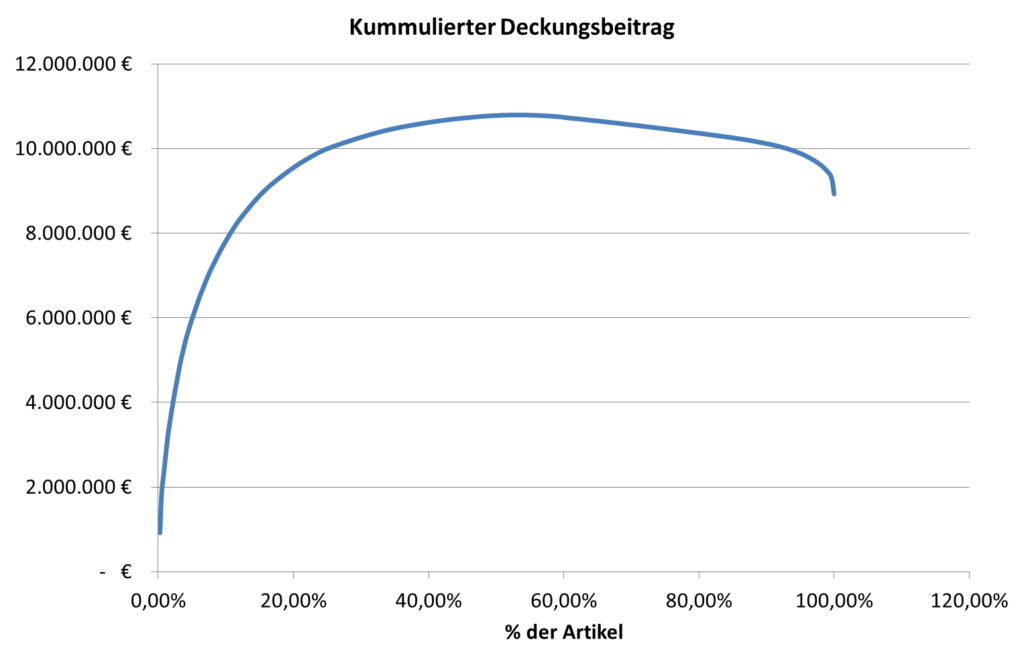

Basic Principle 3 is the first insight to emerge from this form of logistical classification of the product portfolio: A large proportion of the CZ2 articles and many of the CZ articles have to be cross-subsidized by the AX articles. This makes AX articles more expensive and less competitive.

In the second part of this best practice article next week, we will reveal how you can avoid these cross-subsidizations or distribute them more cleverly and escape the assortment constraints.

You are welcome to ask us about the risks and side effects in advance at any time by e-mail: ak@ak-online.de