Now that you have learned a lot in the first three parts, we come to the crowning conclusion:

You already know why and how you should structure and regularly “clear out” your product portfolio and why your stock will otherwise explode at some point (figuratively speaking, of course – unless you store liquid explosives…). You have also already found out how to avoid product range constraints and involve your customers in the portfolio adjustment.

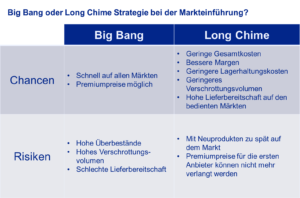

In this part, you will learn that the “big bang theory” for bearing manufacturers is better left as just a theory and has nothing to do with a skillful market launch. And we explain why standardization is the warehouse’s best friend.

In many industries, it is common practice to launch new products on all markets at the same time, and for many products this may not be possible in any other way. Fashion, for example, only has a limited lifespan and must be presented quickly on all markets where it is to be sold. What applies to fashion generally applies to the majority of short-cycle stock products.

Getting a new product into stores everywhere at the same time requires a great deal of effort throughout the entire supply chain :

New product launches with a “big bang”, i.e. in all markets at the same time, require high inventories and high flexibility costs in the supply chain for stock manufacturers, combined with long lead times.

With new products, there is typically the problem of predicting future market demand. If you want to be able to deliver despite uncertainties, you need to stock up on the new products. In the worst case, you need safety stocks in all markets. The required stocks need to be built up before they can be sold, and the necessary components need to be procured, manufactured and assembled. Such a new product piglet must therefore be pressed through the entire supply chain and slowly digested.

Worse still, entire collections of parts often have to be brought onto the market. The queue of suppliers and own production must therefore digest an entire herd of piglets at the same time. Just as the snake has to stretch, so too must the supply chain, which means additional costs for the necessary flexibility.

However, the reality is even meaner than previously described. Not only your company, but also most of your market competitors think and work in the same rhythm, sometimes burdening the same supply chain, the same suppliers, with their herds of piglets at the same time, which drives up the costs of the suppliers and therefore your costs even further.

This strategy would not be absolutely necessary in all sectors and for all companies that introduce products using a “big bang” strategy if they had the courage to break away from lemming behavior.

In many industries, it has long been common practice to test the demand for new products in “test markets”. In the food industry, for example, this is a typical approach taken by many suppliers. In the case of more durable goods, such as technical products or luxury goods, this strategy offers the opportunity to sell the lower material stocks on other markets if a product is not successful on its launch market.

If the introduction is successful, you can ramp up the supply chain. You can use the increasing expansion of the supply chain for products for which high delivery capability and thus a good market supply are important, as is typically the case in the consumer goods sector, in order to satisfy the increasing demand on the launch market before you expand the supply to new markets.

In the case of products for which a certain exclusivity is one of the product features, additional sales markets may be added first or the initial markets may be better supplied, thus further increasing the exclusivity character in the subsequent markets.

However, by discussing how we distribute the growing output of the supply chain to the markets, we are poaching in the area of marketing and sales strategy and we should leave this to the relevant experts. The main thing is for the experts to think about whether a “long chime” strategy is conceivable instead of a “big bang” market launch, in which the markets are served and filled successively and the supply chain can run empty better if the products do not reach the market.

Let’s imagine how beautiful the supply chain world could be if not all products were brought to all markets at the same time, i.e. collection by collection. The result would be much lower flexibility costs throughout the supply chain, lower scrapping costs and better delivery capability. For many companies, such a world would be unthinkable, but time and again there are companies that do the unthinkable, thereby significantly improving their margins, setting themselves apart from the market and thus demonstrating best practice building block 11:

Best practice module 11: Big bang or long chime: Successful companies check whether and how abruptly new products really need to be introduced.

As we all know, not everything about a new product has to be new. New products are often only product variants. Product variants can now be developed in such a way that the variant spread must take place early or late in the supply chain. From a logistical point of view, late variant spreading is better than early variant spreading; the best variant spreading for the logistician is the one that does not take place at all…

Regardless of whether new products are variants of existing products or not. You can always think about using identical parts. The common parts strategy starts with a few standard screws in different products and extends to identical assemblies in different products. It is worth thinking about, because as Basic Principle 12 states:

The fewer different products can rely on common parts, assemblies and manufacturing processes, the more expensive the value chain and supply chain become.

A diversity of variants, where variants are created late in the value stream, counteracts a CZ explosion at finished goods level, which can break the neck of any company. It would be ideal if variants at the finished goods level were no longer stored at all, but were assembled to order. This is a strategy that is possible and common in many industries and for countless companies. This is how the automotive industry works on the European market and how the majority of the machine tool industry works.

A standardized range of variants, in which as many identical parts as possible are used, also prevents the explosion of CZ at component and assembly level.

Starting from an existing broad product portfolio, the path to a standardized range of variants is long and the effort involved is considerable if the concept is not considered right at the start of new product development.

As a best practice strategy 12, we can therefore state the following

Successful companies standardize their range of variants. And you start right at the beginning of the life cycle of a new product by thinking ahead to possible variants.

With this last consideration, we have finally reached the border area between portfolio management, product management and product development and we do not want to cross this border here.