By Prof. Dr. Götz-Andreas Kemmner

It is always the same three performance deficits in the value chain that bring companies to their knees. Why is this the case and how can countermeasures be taken in good time?

1. triggering a crisis versus causing a crisis

There are always crisis situations for companies. Many companies are nevertheless able to hold their own successfully. Others, on the other hand, have to go to insolvency court or be restructured in more moderate phases of recession or even in times of economic upturn.

But why is a company no longer sufficiently competitive? If you ask companies or follow the public discussion in the media, the same supposed causes that lead to liquidity crises dominate time and again, such as

- short-term collapse of markets,

- lack of “loyalty” of the debt capital,

- the international competition,

- Currency fluctuations or

- Export or import barriers.

To a large extent, however, this is just the last straw that broke the camel’s back. The real causes of the lack of competitiveness usually lie elsewhere. As Hauschild pointed out a long time ago, the chain of causes and effects can be traced back from a liquidity crisis through an earnings crisis and a strategy crisis to a performance crisis.

2. the weakest links in the value chains

Ultimately, it is performance deficits that erode the competitiveness of companies. In good times, earnings mask performance deficits, but in bad times these deficits can cost lives. This is precisely where we need to start in order to ensure the long-term competitiveness of companies.

Experience from restructuring and reorganization projects as well as expert analyses show that the problems can always be found at the same points in the value chain!

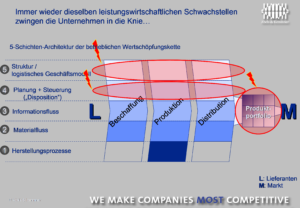

Let’s break down the value chain into five layers (Fig. 1): The bottom layer is the manufacturing process, i.e. what is done on a single production line or machine. The manufacturing processes are characterized by material flows (shift 2) connected with each other. These material flows are supplemented by information flows (layer 3) triggered. The information flows, in turn, are managed at the planning and control level (layer 4) Coordinated (“planned”).

And the planning and control level is responsible for ensuring that the architecture of the value chain (layer 5) is implemented. The result of such a five-layer value chain is the product portfolio. And this must assert itself on the market. The central problems of the value chain are often found in the following three places: in the product portfolio, in the planning and control of processes (layer 4), and in the architecture of the value chain (layer 5).

The three positions therefore require closer examination and entrepreneurial attention.

2.1 The product portfolio

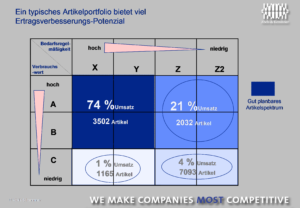

A typical product portfolio, as can be found in many companies on the finished goods side, is structured according to sales significance (ABC) and regularity of demand (Fig. 2).

And this portfolio distribution already shows potential. It turns out, for example, that around 60-80% of sales are often generated with 20-30% of article numbers. At the other end of the portfolio, only 3-4% of sales are achieved with 40-70% of the items, which requires a considerable proportion of the total stock. At the bottom right of the product portfolio, in the CZ and CZ2 articles, hardly any money is earned. In process cost analyses, we repeatedly find that these items, even if the contribution margins still appear positive, burn money when costs are allocated precisely: High inventories and therefore capital commitment in relation to sales; high processing and administrative costs; high risk of scrapping.

It is astonishing that very few companies – and not just the economically weak ones – maintain their product portfolio properly. For this reason, it is usually also possible to carry out a so-called “downsizing” when companies are restructured: This involves shedding a loss-making and disproportionately costly part of the product portfolio. At the same time, the associated machinery, inventories, infrastructure and personnel can be reduced and the company returns to profitability. Regular critical maintenance of the product portfolio could avoid such dramatic steps and the associated staff reductions. On the contrary: even higher yields would be generated!

2.2 Planning and control

The fourth layer is also often fraught with weaknesses: the planning and control of the value chain. And this is sometimes surprising, because despite many years of experience in the use of PPS and ERP systems, many companies still do not have an end-to-end planning chain from sales planning to production control; there are often manual steps in between in the form of Excel planning, for example. Instead of using the automatic planning mechanisms of the ERP system, work is done by hand: The ERP system only serves as a golden typewriter. However, what was still possible 30 years ago with a few and simpler products and simpler production processes using wall-mounted planning boards can no longer be maintained today. The importance of efficient scheduling and production control is systematically underestimated in most companies. 153 billion in excess inventories during the economic boom in Germany is just one indicator of the inefficiency of replenishment processes. Without efficient and automated planning and scheduling processes in key areas, there can be no sustainable profitability! In many restructuring projects, and not only there, the liquidity required for the implementation of measures can therefore be obtained simply by reducing inventories! For many of those involved, the fact that this money could have been used to do completely different things in better times is often sobering.

2.3 Lack of coordination of business models

Even if many entrepreneurs are not aware of it: Their businesses don’t just have a corporate business model. They also have a logistical, which can be seen in Fig. 1 is composed of six components. The two business models often do not work in sync. This is the third major weakness in the value chain: while the corporate business model is constantly being adapted to market requirements, companies rarely change their logistics business model. And this can lead to fatal imbalances – even for up-and-coming companies (Fig. 3).

The errors that can arise from a lack of coordination between the two business models are manifold. A high number of variants that are created far too early, at the beginning of the first production steps, is a typical result of unsynchronized product development. Excessive readiness to deliver items that are rarely in demand is often due to misunderstood customer satisfaction requirements, because not every part always has to be available immediately. There are also incorrect logistical decoupling points or a lack of market-synchronized production. And these are just a few examples of a lack of alignment between the logistics business model and the corporate business model. The asynchrony between the corporate business model and the logistics business model leads to inefficiencies, which become apparent in the form of inventories, overcapacity and other wasted resources and ultimately increased costs. Synchronization therefore holds significant levers for substantially strengthening the entire value chain.

3. causes of mismanagement

Why are these problems in many companies not rectified in good time and in good times? In practice, there are four main reasons for this mismanagement:

3.1. Internal target systems cancel each other out

Internal target systems are now widespread as part of corporate management by target agreement. Not only in large companies, but increasingly also in SMEs. The aim is to reduce the purchasing volume in relation to sales. Production is intended to increase plant capacity utilization. Sales should increase turnover and logistics should reduce inventory costs. Each individual target sounds nice, but as the individual targets are not independent of each other, improved targets in one area are often at the expense of other areas. In this way, area egoisms are strengthened and everyone concentrates more on their own optimum and less on the overall optimum. As a result, the improvement measures that have the greatest impact across the value chain and can contribute the most to increasing a company’s competitiveness fall by the wayside: the adaptation of the logistics business model as a whole, the planning of the value chain and the adaptation of the product portfolio. For the same reasons, many companies’ product portfolios are also growing like weeds, without the expenses really being in proportion to the income.

But how can this problem be solved, given that target agreements are an essential element of management? There are two starting points:

On the one hand, consistent target systems are required. Consistent means that causation and responsibility are brought together. In addition, managers must be measured more by their contribution to the company’s overall performance than by partial successes in their area.

In addition, the functions within the company that bear cross-sectional responsibility in the value chain, such as logistics and supply chain management, must be strengthened. The consequence of this change in perspective is that traditional specialist departments are becoming service providers for the entire value chain.

3.2 Lack of expertise Many companies lack the knowledge of how to structure the value chain correctly, and not just in crisis situations. We are used to constantly working on partial optimizations. However, there is a lack of expertise for the overall concept in order to develop sufficiently differentiated solutions. Most managers only know a few design variants for certain tasks in their area of responsibility, with which they have gained experience in their professional life. They fall back on these again and again, at best modifying them slightly, although the internal company environment is always different. They are subsequently unable to assess the strengths and weaknesses of these solutions, especially if the operational conditions on the market change. They also usually lack sophisticated tools for designing and interpreting the right solutions. Last but not least, they also lack the time to develop, test, calibrate and optimize such tools. It is therefore often necessary to call on external experts, and not only in the event of a crisis or restructuring!

3.3 Delays in decisions

It is not always possible to reach a consensus. Nevertheless, decisions have to be made. However, such strong leadership is lacking in many companies: If there is no consensus on a problem or a solution in the management circle, discussions continue at best, but no decisions are made, nor are experts called in to summarize the problem and develop a solution. And if employees resist a change, it is often delayed instead of convincing them or making it clear to them that there is no alternative.

Such behavior can lead companies into crises, and in restructuring cases we almost always come across individuals in the company’s management circle who are aware of the problems but were unable or unwilling to push through decisions – for whatever reason.

3.4 Overload

In most companies, managers and employees are notoriously overworked. As a result, decisions are often not carefully prepared and concepts are insufficiently developed. This results in dangerous undesirable developments. But why is that? Experience shows that, on the one hand, money is being saved on every head. On the other hand, work is still too cumbersome. Ultimately, too much effort is being put into product segments in which too little revenue is being generated. And this brings us back to the product portfolio and the point at which we started analyzing the weak points in the value chain.

4. conclusion: action is needed

Market requirements and demands on the value chain do not usually change so quickly that it is impossible to keep up. Companies can therefore survive a few months of adjustment when changes in the market or even an economic crisis occur. However, a company can only be and remain competitive if it has eliminated the three central weaknesses in the value chain described above and developed measures to prevent them from arising again.

References:

Hauschildt, Jürgen: Crisis diagnosis through balance sheet analysis, Cologne 2000

KEMMNER, G.-A.: Learning from Apple’s minimalism In: Productivity Management 17(2012) 4, p. 40

Abels & Kemmner: Overstock analysis Germany 2009.

Source: [intlink id=”2044″ type=”post”]https://www.ak-online.de/2009-03/pm2009-1/[/intlink]

Wickinghoff, Constantin (1999): Performance measurement in logistics. Fundamentals, concepts and starting points for evaluating logistics processes, University of Cologne, p. 3

Cf. Breisig, T. (2007): Entlohnen und Führen mit Zielvereinbarungen, Methoden, Chancen und Risiken,

Knowledge for Works and Staff Councils, 3rd edition, Frankfurt am Main, p.23.

Koch, M.: Development of an information supply concept as a basis for company-specific business intelligence solutions for industrial companies. Lohmar 2014, p. 46

Weber, N.; Fohrholz, C.: Business Analytics – Dominance of Business Intelligence and Lack of Integration. In: ERP Management, 3/2013, p. 30-32

Days of absence due to burnout have almost doubled since 2000. DIE ZEIT from June 7, 2012

Further information on this topic can be found here:

- Best practice rules for product portfolio management