In the first part of this article in the last issue of POTENTIALE, we explained that

- Overstocks are sometimes like candy. They flatter the soul and soothe, but are unfortunately bad for the girth,

- There are always inventory drivers in every company that need to be identified on a regular basis,

- You can avoid overstocking through precise sales and demand forecasts,

- Precisely defined sets of rules and simulation mechanisms are preferable to the gut feeling of even the most experienced dispatchers,

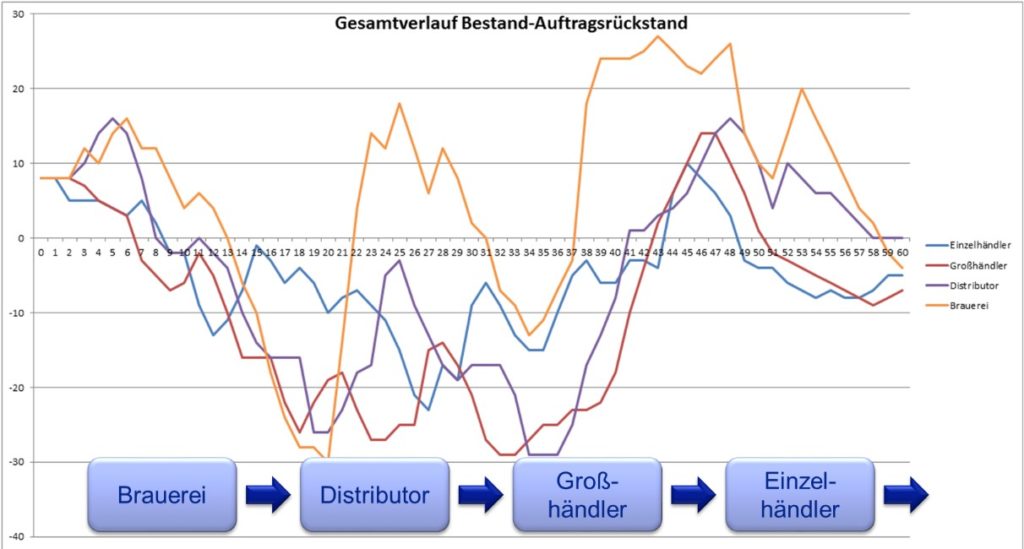

- Manual, hectic oversteering in the supply chain causes a whip effect that can throw even the best planning off course.

Part two of our article begins with the correct planning decoupling between inventory and planning levels.

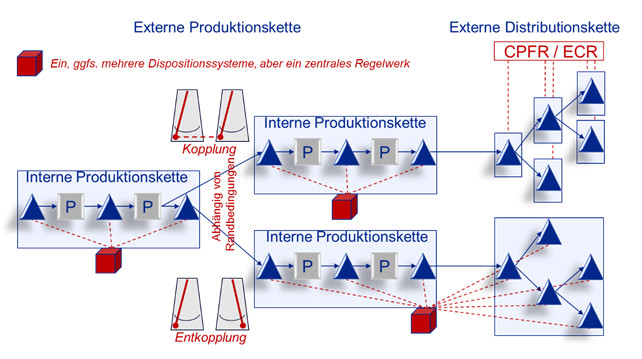

On the distribution side, from the central warehouses to possible regional warehouses to any branches or “points of sale” behind them, many companies still work with conceptually and personnel-decoupled disposition levels. Each regional or national leader has its own strategy, each store manager decides on his own replenishment. However, this represents the first step towards dispositive anarchy.

Basic principle 6: Decoupled decisions in internal and external distribution chains break the flow of goods.

If you are not familiar with the so-called “Beer Game”, you should give it a try. In this simulation game, a supply chain from a brewery via a distributor, a wholesaler and a retailer to the customer is depicted. In the individual storage levels, decisions must be made in each game round about the quantities of beer crates to be reordered so that stocks remain as low as possible and the delivery readiness levels as high as possible. Each warehouse level only knows the current orders from the respective customer and decides independently which quantities to reorder from the supplier. It’s exciting and entertaining to see how the disposition quantities and inventories build up.

This Beer Game corresponds to the typical strategy in a supply chain in which each warehouse level acts independently and autonomously. Concepts such as “Forward Sourcing”, Efficient Consumer Response (ECR) or Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment (CPFR) are used in an attempt to capture such planning chains. This is not easy, as many interests and egoisms of independent parties that do not obey a common master have to be reconciled. In many of our companies, however, there are indeed distribution chains that report to a common head and whose individual behaviors are ultimately consolidated into the company’s overall result.

At least in these distribution chains, it is possible to work against arbitrariness and top performers in inventory management do so. The way to achieve this is through centrally controlled replenishment of the various distribution levels, based on a correspondingly sophisticated and continuously optimized set of rules.

Individual warehouses in the distribution chain often represent legally independent units that also bear independent responsibility for results. They usually see the planning of their own stocks as a sovereign right and competitive factor: “If I am responsible for the results of this national company, then I must also be able to plan my stock as I see fit,” is a typical reaction to the suggestion of central replenishment. In practice, however, it has been shown time and again that you can achieve more with less stock in total, but distributed over the right items. Material availability at the individual storage levels can be ensured by means of delivery service agreements between these levels and the central planning department. This must be supported by disciplined exception planning for projects, campaigns or other special requirements.

Best practice module 6:

Sustainable inventory management in a distribution chain can usually only be achieved through centrally controlled replenishment. Responsibility for exception planning and delivery service agreements takes the place of decentralized inventory responsibility for the externally planned warehouse levels.

A supply chain consists not only of distribution relationships in which different warehouse levels are linked via transportation processes, but also of long-term procurement relationships between a customer and a manufacturing supplier. In these cases, the logistics process does not only consist of a stock transfer relationship between the supplier’s finished goods warehouse and the customer’s incoming goods warehouse. The supplier may not even store the part to be delivered as a finished product; in any case, the warehouse from which the item is delivered to the customer is replenished by a production process.

In lean management, it is often recommended in such cases to manufacture in step with the customer, i.e. to link both production stages in terms of time and quantity.

Provided the right conditions are in place, this also works very well, as we shall see. In many cases, however, you are missing out on opportunities for inventory reduction and economic efficiency, because you better pay attention to

Basic principle 7: The logistical system of a company works according to its own unmistakable rhythm.

From an inventory management perspective, there is still considerable potential in cooperative collaboration between customers and suppliers to reduce inventories and improve security of supply. The possibilities start with drawing parts and product specifications and range from the avoidance of storage stages to administrative integration.

Bringing your own production into a cycle can be a very effective approach to getting material flows to flow evenly and thus also simplify inventory management. Adopting the customer’s pace is often too simple a guiding model, as in many cases the supplier’s production chain does not work specifically and exclusively for the customer’s production chain. We know from sports medicine that jogging together is not always an advantage: every runner has to find their own rhythm according to their own condition.

A linkage between customer and supplier exists not only when the supplier works in step with the customer, but also in a weaker form when the supplier has to react immediately to the customer’s order or call-off in order to meet an agreed delivery deadline.

With long-term business relationships and regular deliveries, the decoupling of supplier and customer often harbors great economic potential. It can be more cost-effective and more efficient in terms of inventory to manufacture to your own cycle time or to emancipate yourself from the customer by maintaining an inventory buffer. A classic finished goods inventory is also used for decoupling, but then if necessary. at the expense of higher inventories. A VMI (Vendor Managed Inventory) concept is a clever and very effective instrument for decoupling.

In typical VMI mode, replenishment of the customer warehouse is carried out independently by the supplier. The customer is spared the scheduling work, the supplier gains scheduling freedom, as he can decide more independently on his subsequent delivery with regard to delivery date and delivery quantity. The supplier assumes the capital commitment of the stocks held by the customer, the customer assumes their storage and management and typically also the economic risk. VMI concepts are not a bad deal for suppliers. It’s astonishing that so many people are still resisting this.

The situation is different if the supplier’s production chain is really specifically geared to the customer’s production chain, as is very often the case in series production and especially in the automotive industry. In this case, the strategy of very close cooperation is advantageous, especially as it has already been designed into the production chain. If the production processes of the customer and supplier are very precisely coordinated and both are very stable, just-in-time (JIT) or just-in-sequence (JIS) processes can achieve very low inventories with high delivery readiness. On the supplier side, however, the principle of pull control, which is sacrosanct in lean management, is dispensed with in favor of targeted push control so that the materials flow in at exactly the right moment.

Best practice module 7:

In a production chain of economically independent companies, inventories, delivery readiness and profitability of the parties involved can usually be best optimized through decoupled processes. In the special case of precisely coordinated production lines, however, the coupling principles of an internal production chain apply again.

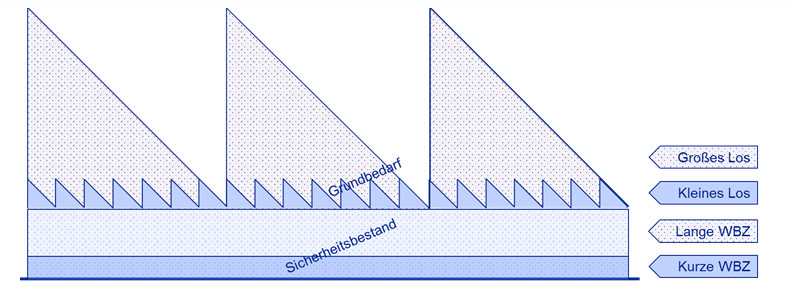

As discussed, production in cycles offers great advantages for the economic efficiency of production and for inventory management in internal production chains and in specially coordinated external production chains. Unfortunately, items with large batches and long lead times all too often stand in the way of this ideal…

Basic principle 8: Items with large batches and long lead and delivery times are junk food for the value chain – cheap to have but difficult to digest.

Who among us does not work with Asian suppliers? Many products can only be sourced in Asia, while for others the price advantages of Asian suppliers leave no choice. However, Asian sourcing also has considerable disadvantages. Let’s forget the not-so-rare cases in which the price advantages of Asian suppliers are already eaten up by the travel costs of the buyers. From a logistical point of view, the effect is more serious, which is usually due to long replenishment times combined with large procurement lot sizes: regardless of whether these are the consequences of minimum order quantities, freight cost optimization or the obligation to fill containers.

Items with large batch sizes and long replenishment times always cause high stock fluctuations with high average stock levels. On average, the large lots have a much more dramatic effect than the long replacement times. Doubling the replenishment time does not necessarily mean that the covering times will also increase. However, the required safety stock increases by approx. 40 %. Doubling the lot size, on the other hand, leads to a doubling of the base stock. The more irregular the demand for items, the greater the impact of the safety stock effect; the more uniform the demand, the greater the impact of the change in base stock.

If you work with large batches not only in procurement but also in production, the material flows through production in large batches. This is associated with the risk of temporary capacity bottlenecks that slowly creep through the value chain like a piglet being swallowed by a snake. Such blockages lead directly to higher circulating stocks in production.

Of course, you can’t make production and procurement batches as small as you like, you have to keep an eye on the total costs, but then please really look at the total costs and not just the purchase prices. It makes a huge difference whether inventory management and logistics strategy are geared towards continuously working on reducing batch sizes and replenishment times or whether you accept both parameters as more or less a given. Behind these two “inventory management cultures”, the gap is widening between the absolute top performers and the rest of the companies; the former are continuously working to grind up the material flow and thus increase the flow rate of their production (ratio of processing times to throughput times). The higher the flow rate, the more even the flow of goods and the lower the stock and circulating stocks.

Figure 2Within economically linked companies and in the distribution chain, scheduling levels should always be synchronized via a central set of rules.

Best practice module 8:

Sustainable inventory management requires an easily digestible material mix consisting of small production and procurement batches and the shortest possible replenishment times.

Delivery bottlenecks can occur in any supply relationship, regardless of whether it is decoupled from the planning system or operated via a central planning control system. In the case of dispositively decoupled supply chains, one encounters in such cases…

Figure 3The smaller the procurement and production batches, the smoother the flow of goods. The shorter the replacement times, the lower the safety stock.

Basic principle 9: If everyday goods become scarce, and in the business-to-business sector this applies to practically all goods, then demand is the first to be overstated.

We all know this from the food sector: the threat of winter storms, but also several holidays in a row, occasionally lead to hoarding. However, the spook is usually over quickly.

This also applies to the industrial value chain if bottlenecks prove to be only temporary. The situation is different if the shortage lasts for a longer period of time and customers cannot switch to substitute products.

Many suppliers who can no longer meet the market demand for such “no-alternative” items naturally start sending partial deliveries to customers. This drastically eases the supply situation, provided that the bottleneck is only temporary, as the missing quantities are delivered at short notice. However, if a bottleneck exists for a longer period of time, typically several months, the supplier will never be able to meet customer requirements.

From the customer’s point of view, the delivery situation then looks like a quota system and some suppliers actually handle shortages in this way. The customer has ordered 1000 units and receives 200. A typical reaction of customers to this situation is a simple rule of three: If I receive 200 for an order of 1000 pieces, then I will receive my required 1000 for an order of 5000 pieces. It’s easy to imagine chaos breaking out when all customers react this way…and many customers do.

It is also not easy for a buyer to put the advantages of his own company behind those of other customers who do not understand. As a result, supposed market needs arise that do not correspond to reality. Such cycles are well known in the semiconductor industry. In the worst case, they lead to suppliers drastically increasing capacity. However, as soon as real demand can be satisfied again due to the higher production capacity, the artificial increase in demand collapses again. Before this happens, however, many customers are flooded with high delivery volumes.

The solution to such persistent supply bottlenecks is actually obvious, but it must be applied consistently: It is right to quota the allocation quantities to customers, but on the basis of past orders at times without relevant supply bottlenecks and not on the basis of current customer orders. If this procedure is clear to all buyers, there is no longer any reason for order volume inflation and the threat of a pig cycle is significantly dampened.

Best practice module 9:

In the event of long-term capacity bottlenecks, deliveries to customers must be quoted on the basis of past delivery volumes.

In the next issue of POTENZIALE, you will find out what this means for the customer-supplier relationship and what impact the behavior of business partners has on your supply chain.

Further information on this topic can be found here:

- 13 best practice criteria for sustainable and holistic portfolio management – Part 1

- 13 best practice criteria for sustainable and holistic portfolio management – Part 3

- Safety stocks: the five-point plan

- Best practice rules for efficient sales forecasting