By Prof. Dr. Götz-Andreas Kemmner

While part two of our article has taught you the correct decoupling of inventory and MRP levels and explained the optimal coordination of lot size and replenishment lead time, we now move on to the final steps on the way to perfect inventory management: What are the consequences of different goals for the individual partners along the value chain and how do you coordinate with your business partners so that their behavior has as little impact on your supply chain as possible?

Unfortunately, the customer-supplier relationship in the supply chain is not only strained by exceptional situations such as persistent delivery bottlenecks, but also by the behavior of the (supposed?) partners in everyday operations, see… Basic principle 10: When purchasing and sales meet, it is all too often about tactical maneuvering or leveraging power rather than constructive collaboration. It is in the nature of things that the purchasing department tries to achieve the lowest possible prices for the products and qualities required by the company. It is also in the nature of things that the distributor wants to achieve the highest possible prices for the products and qualities it offers on the market. We all know what happens when the supplier’s sales department meets the customer’s purchasing department: everyone tries to gain negotiating advantages and use their own negotiating power. It is therefore particularly uncomfortable when one of the two parties has significantly more power. But in many business relationships, even business partners at eye level try to constantly catch each other out in misconduct or conceal their own misconduct in order to strengthen their own position in the next price negotiations. This behavior is all the more pronounced the more sales and purchasing are responsible for day-to-day business on both sides. Work is more cooperative where scheduling talks to scheduling and logistics talks to logistics. In this way, many coordination problems can be solved “at the working level”, so to speak, before they lead to conflicts at the “ministerial level” and thus usually to increased inventories.

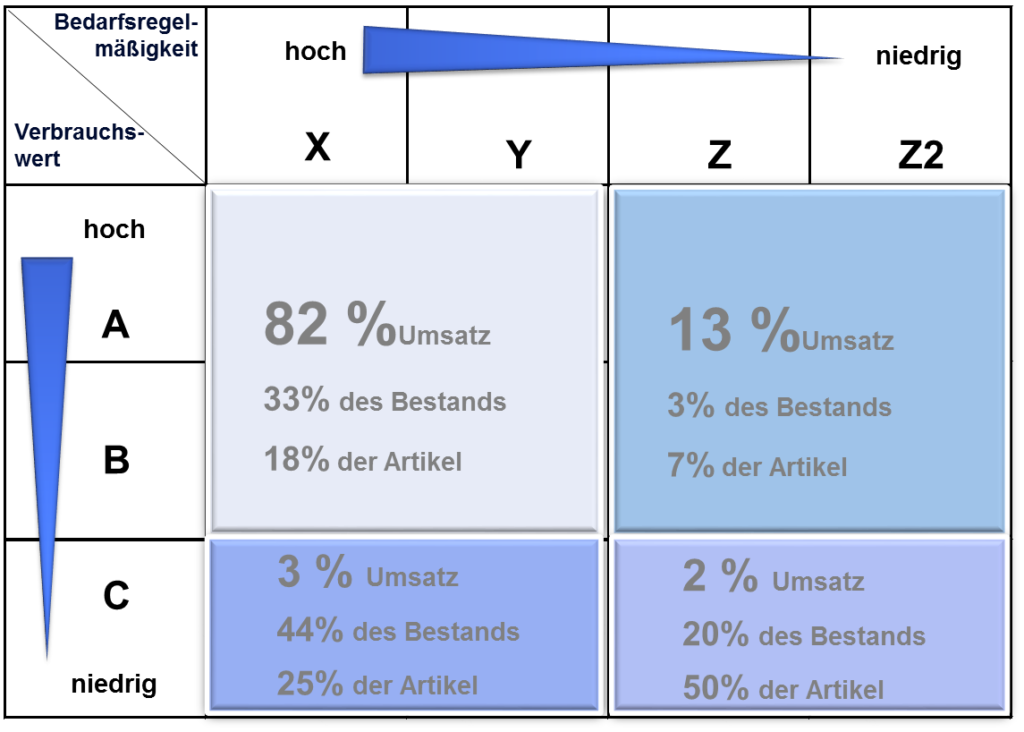

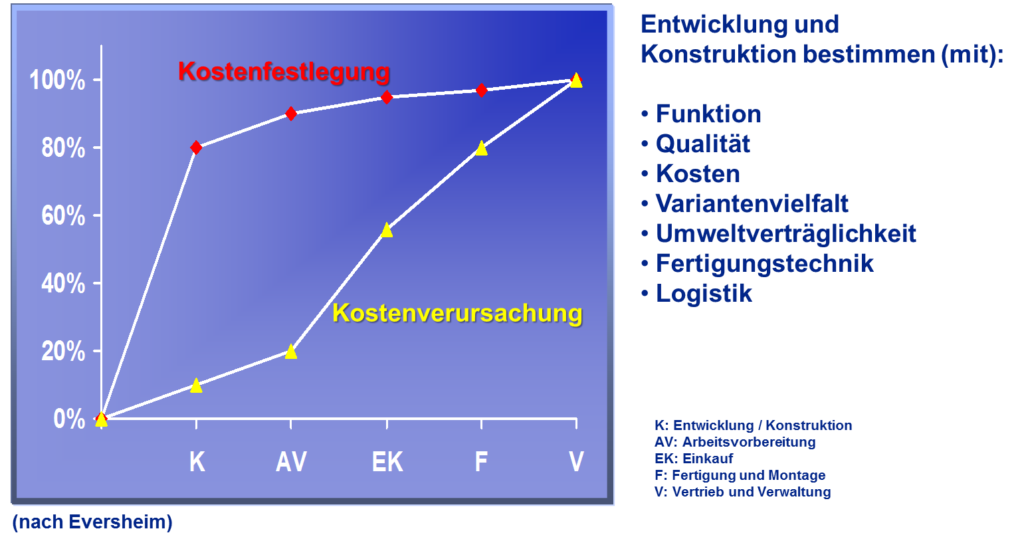

Best practice module 10:Sustainably effective inventory management requires objective and cooperative collaboration with the central suppliers, in which the costs of the supply chain are shared by all parties. If we look beyond the warehouse gate at the variety of products in our raw materials, semi-finished goods and finished goods warehouses, we quickly realize… Basic principle 11: Small cattle in the product portfolio usually make a lot of muck, but little turnover and even less profit. In a typical product portfolio of a stock-keeping manufacturer or trading company, 20% – 30% of items generate 60% – 80% of sales (A-B/X-Y parts), while at the other end of the portfolio, 20% – 40% of items often only generate 2% – 3% of sales (C/Z-Z2 parts). While we find turnover figures of 12 – 24 and sometimes far beyond for the high-flyers, the stock of many of the exotics does not turn once a year. But even this long tail of exotics has to be managed and stored. If this “long tail” is procured on an order-related basis, it does not pose a significant problem for inventory management. However, order-related procurement is often not possible for various reasons. It is then necessary to find sensible strategies to reduce stocks and handling costs. Contract manufacturers also have to deal with this kind of product portfolio distribution, not at the finished goods level, but at the purchasing or assembly level. One solution here is short production throughput and replenishment times for these exotic parts or, in some cases, C-parts management, which is primarily geared towards C/X-Y parts, but can be used for some C/Z-Z2 parts with short replenishment times. However, a considerable proportion of these C/Z-Z2 parts consist of drawing parts, for which C-parts management usually does not help. The long tails in our companies’ product portfolios have a story, and like all stories, it starts at the beginning. In the case of a product or component, this means: when identifying or assuming a solution to a problem in which the market is interested. In order to be able to offer the solution, variants are split up or completely new parts or products are developed. With new product launches, it is in the nature of the business that we first build up stocks in order to be able to react quickly to the expected increase in demand and thus give the new product a chance on the market. If the product has had its chance and has not been able to make use of it, then it is logical to part with this product again. From a logistical perspective, there is a lot to optimize in the context of product portfolio management, for both new and discontinued items.

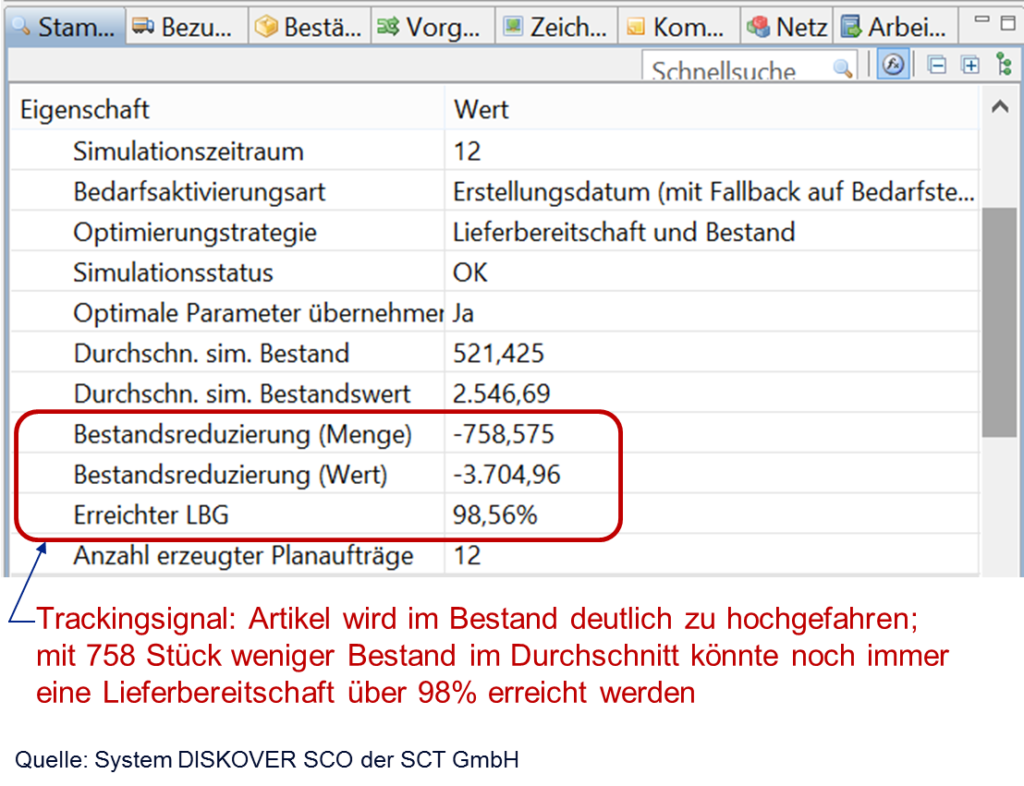

Consistent target inventory management is the lane departure warning system for inventory management. It gives users a guiding signal so that they can always find their way back to the predetermined path of readiness for delivery and inventory and shows managers where and how much action is required. Inventory management is a holistic task. If you want to achieve sustainable results, you need stamina and the right tools and methods. Perhaps you have already implemented many of the best-practice modules described, or perhaps you still have a lot of work to do. It is work that is worthwhile from a corporate strategy perspective, as a 20% reduction in inventory improves net profit in an average company just as much as an increase in turnover of around 10%. Further information on this topic can be found here: