Overcoming seven hurdles

Production in the right batch size

In practice, lot-sizing methods are rarely used to reduce the costs of warehousing, procurement and production. This can often save a lot of money. In order to exploit the potential of the methods, users must be aware of the limitations of the approaches – because they cannot take all operational interdependencies into account. Methodological expertise across the entire supply chain is therefore required for precise application.

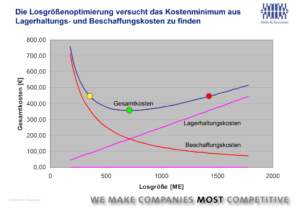

Economical batch sizing methods are used to calculate the minimum total costs from warehousing costs on the one hand and procurement and set-up costs on the other, in order to minimize the total costs of the value chain. Larger batch sizes in procurement and production lead to higher inventories and therefore higher warehousing costs. These generally increase in proportion to the batch size, while procurement costs fall in inverse proportion (see figure above). Where the two cost curves intersect is the minimum total cost.

Economical batch sizing methods are used to calculate the minimum total costs from warehousing costs on the one hand and procurement and set-up costs on the other, in order to minimize the total costs of the value chain. Larger batch sizes in procurement and production lead to higher inventories and therefore higher warehousing costs. These generally increase in proportion to the batch size, while procurement costs fall in inverse proportion (see figure above). Where the two cost curves intersect is the minimum total cost.

Cost types for lot size optimization

The basis of all economic batch size calculations is consequently the determination of inventory costs as well as procurement and set-up costs. Warehousing costs consist of interest on tied-up capital as well as costs for aging and wear, loss and breakage, transportation and handling within the warehouse, storage and depreciation as well as warehouse management and insurance. Procurement costs can include Ordering costs, rebates, bonuses, discounts, additional costs for unfavorable order or production quantities, transport, insurance and packaging costs, order processing costs. Slightly fewer cost types are usually included in the setup costs. In practically all cases, these are imputed costs and it must therefore be determined on a company-specific basis and from an entrepreneurial perspective which imputed costs are to be recognized and at what level. There are now five hurdles to overcome on the way to economical batch sizes. The first hurdle is to consider the correct cost types and their amount.

The classic ‘andler’ usually falls short

In economic lot-sizing methods, a distinction is usually made between static methods and dynamic methods. The central static method is the Andler method. The formula developed by Kurt Andler in 1927 determines the minimum of the total cost curve based on the assumption that the total quantity required of an item in a planning period, for example one year, is known. The formula derives an economic batch size from inventory costs and procurement costs, which remains constant over the planning period and must be called up at a constant rate in order to actually achieve the targeted minimum costs. The problem: In practice, production or order requirements are not constant over a planning period, but follow each other irregularly and vary in amount. This is particularly clear in the case of planned requirements for planned MRP. But even with the reorder point procedure, the quantity required is usually not regular, as a look at past data shows. Dynamic economic lot-sizing methods attempt to meet the challenge of irregular requirements by focusing on the actual demand situation.

The most common procedures in this group include

- the part-period method or piece-period equalization method,

- the unit cost method or the sliding economic lot size method,

- the Groff process,

- the Silver-Meal process and

- the Wagner-Whitin method.

All the methods listed – with the exception of the Wagner-Whitin method – are to be understood as approximation methods that ‘gather’ economic lots sequentially, order by order, from the requirements time series. Only the Wagner-Whitin method determines the optimum across all order quantities and production lot sizes in the planning period.

The Wagner-Within approach is very precise

The Wagner-Whitin process was developed back in 1958. As it was too computationally intensive for the first materials management programs and could not be used manually, the above-mentioned approximation methods were developed in the following years. The deviations of the approximation methods from the exact Wagner-Whitin method can be very significant, as can be seen in the figure above. Most ERP systems do not support the Wagner-Whitin process. However, it is available in many add-on systems for scheduling. In practice, the Wagner-Whitin method cannot always exploit its theoretical advantage over the approximation method or the Andler method, as the structure of the planned requirements changes over the planning horizon from MRP run to MPR run and the method runs behind a ‘moving target’, so to speak. Nevertheless, companies usually overcome the second hurdle of economic batch size optimization best if they rely on the Wagner-Whitin method for planned scheduling. Simulation systems can be used to determine which economic advantages can be achieved by using which economic lot-sizing method before the economic lot-sizing methods are used in practice.

In this way, it is also possible to identify the items that offer the greatest economic benefits. Such a simulation can overcome the third hurdle of economic batch size optimization, namely to start where the greatest economic effects are achieved. In order to be able to use lot-sizing methods profitably in practice, other aspects must also be taken into account: All classic economic lot-sizing methods consider single-stage, single-product production with unlimited capacity.

This is not taken into account when calculating the batch size,

- that several products usually run over a single production capacity and

- that the economic lot size at one stage of the value chain can have a negative impact on upstream or downstream stages of the value chain.

Particularly in production, but also to some extent in procurement, these boundary conditions must also be included in the design of batch sizes. If the combination of economical batch sizes on a production capacity leads to capacity bottlenecks, the batch sizes must be increased to such an extent that the production capacity is sufficient again. In procurement, on the other hand, it may be necessary to reduce economic batch sizes so that all requirements fit into the available transport unit.

After five hurdles comes the freestyle

The fourth hurdle in economic batch size optimization is therefore capacity balancing. It may also be necessary to coordinate batch sizes in a chain of successive scheduling levels. Making the right batch size trade-offs between scheduling levels is the fifth hurdle to overcome. To a certain extent, these five hurdles mark out the compulsory course for batch size optimizers. In addition, there is the freestyle: the sixth hurdle can be understood as the division into equal work content. As a seventh hurdle, lot-size-dependent throughput times can be taken into account, as circulating stocks in production can also cause significant warehousing costs.

One formula is not enough

In practice, many companies shy away from the effort of setting economic batch sizes correctly once they have realized that simply applying a formula is not enough. In doing so, however, they are giving away considerable potential for economic optimization. With a structured approach, a holistic view and the use of suitable tools, it is actually quite easy to salvage.