Below you will find the first part of a new best practice article by Prof. Kemmner. This time, the topic is when a production kanban makes sense and how best to introduce and use it:

Surveys show that almost every company uses Kanban as a control solution. However, if you take a closer look, you realize that most companies only use Kanban to replenish stocks of assembly materials from the warehouse. In most cases, a two-container solution is used: one container is refilled while the assembly parts are removed from the second container. The refill container is returned in good time before the contents of the second container are used up.

The number of companies using Kanban in production is significantly lower. Production Kanban offers a number of significant advantages over the “conventional” control methods of reorder point control and plan-based scheduling. Before we look at these benefits, let’s take a quick look at what makes a production kanban system tick:

Production Kanban is significantly more demanding than the “baby Kanban” of assembly replenishment. A production scantling system must be able to cope with different batch sizes from one production stage to the next. Despite all efforts to reduce set-up times and set-up costs, production batch sizes in most companies are significantly larger than one piece. For this reason, collective kanban is used in production. The incoming kanban types are first collected by the supplying office. Only when a certain number of cards reaches the so-called “red area” is the production of the production batch triggered via the collected cards. To make the entire system a little smoother, a “yellow area” is usually defined, which is already reached with a smaller number of cards. From the yellow area onwards, the supplying location may re-produce, from the red area onwards it must produce.

Despite the preceding explanations, I assume that you are familiar with the mechanisms of a kanban system in general and a production kanban in particular, at least from the literature.

Stable production control

What is little discussed in the literature are the reasons why a properly implemented production canban system works so reliably and successfully. In general, material availability is significantly better after the introduction of a production kanban, despite considerably lower stock levels: In many cases, 20-30% stock reductions are achievable.

If we visualize how a clean Kanban introduction is carried out, the success factors quickly become clear:

- The disposition parameters of a kanban system are carefully determined and not just “quickly” gauged.

- Production capacities and any fluctuating production requirements are better balanced.

- Before switching to Kanban, potential disruptive factors are identified and largely eliminated.

- The Kanban mechanism separates planning (dimensioning of the control loops) and execution (largely mechanical processing of the Kanban by production). Production requirements are triggered virtually automatically and processed first-in-first-out.

- In the case of the inventory limit at the end of the financial year, the circulating stocks in kanban systems are often not reduced as much as with articles that are planned differently.

- The physical Kanban mechanism copes better with practical disruptions than classic scheduling procedures. These are dependent on correct book inventories in the ERP system. In the event of sloppy or late bookings – both of which are said to have happened before – the classic procedures calculate with incorrect material availability.

The advantages of a kanban system in production described above already indicate that the introduction of production kanban is much more demanding than is generally assumed. We have therefore developed a whole series of best-practice building blocks for a successful production Kanban from numerous projects.

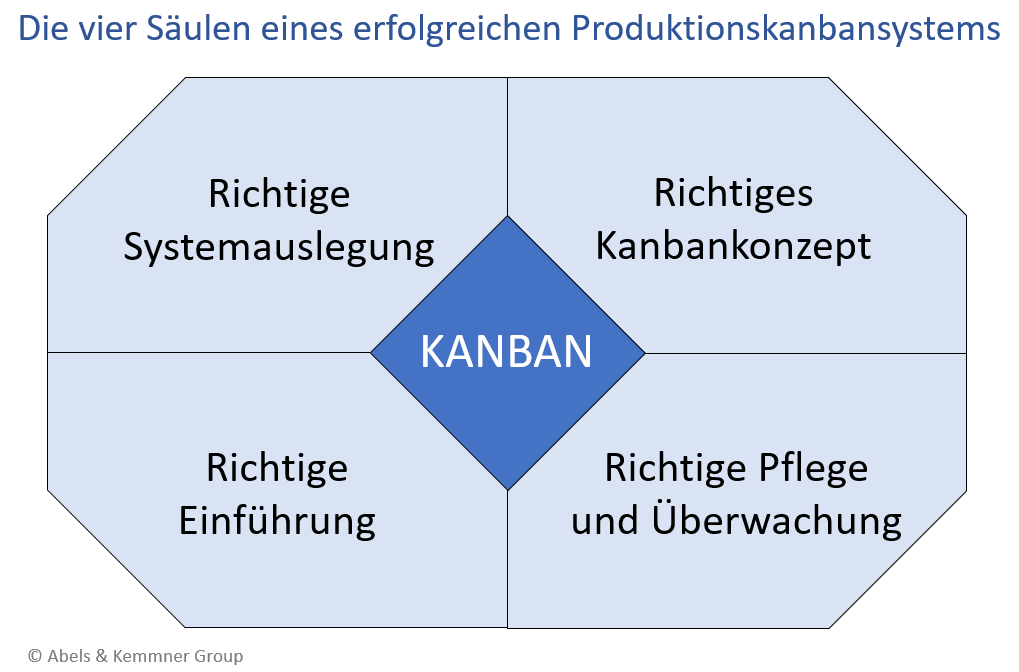

These best-practice modules can be assigned to the areas of correct system design, correct kanban concept, correct implementation and correct maintenance and monitoring.

Figure 1: The four pillars of a successful production channel system

The correct design of the Kanban system

Basic principle 1: There is a lot of brainware in simple solutions

Operating modern smartphones is (for the most part) child’s play. We hardly remember that the world of smartphones was once dominated by Nokias and Blackberries before two companies from California made phones really smart and radically simplified the complexity of operation. Behind the simple operation of today’s smartphones are complex considerations, many tests and sophisticated technology.

Numerous companies have already fallen into the simplicity trap when introducing Kanban because they thought that a production Kanban was as easy to introduce as a two-bin Kanban. But remember: what is ultimately easy to use and looks simple is rarely so simple in concept and production.

As best practice building block 1, we must therefore state directly: A permanently successful production Kanban requires a well-considered and competent introduction

Basic principle 2: “42” is not the answer to all questions[1]

Some proponents of lean management tend to sell you Kanban as the production control principle of the 21st century. This is probably based on the ideal of a simple life in the production world that many people dream of. In science fiction, “42” may be the answer to all questions about life, the universe and everything. In reality, however, there is no standard answer to all the world’s problems. What did you think of a plumber who wanted to repair your heating system using only a pipe wrench? “Anyone who only has a hammer as a tool,” the sociologist Paul Watzlawick once said, “sees a nail in every problem.”

If you are aiming for a production Kanban that functions sustainably and economically, you should not use the Kanban hammer to smash your entire existing production control system. It is better to concentrate on those items that are really suitable for the Kanban application. First of all, the fluctuation in demand plays a role in Kanban suitability, which is usually evaluated in logistics with the help of an XYZ classification. X and Y parts are in principle suitable for edging.

In practical application, it has also proved useful to limit the production kanban items to the A and B parts of the semi-finished products in an initial delimitation. The reason for this is the generally large number of C-items and the resulting space problems for a conventional card kanban. A conventional card kanban can work without problems with an enormous number of kanban types – we have already introduced solutions with well over 15,000 cards, but not with an enormous number of material numbers that accumulate at one supplying location. Mechanical Kanban boards take up a lot of space and become very confusing. Kanban solutions with electronic, automatically monitored kanban boards have no problems with this. Nevertheless, you should stick to the principle when introducing a production kanban. In addition, you are of course free to ensure that more and more of your production parts are suitable for kanban.

We note best practice building block 2: Successful kanban systems in production concentrate on AB/XY articles.

Basic principle 3: Consumption series of semi-finished products and purchased parts do not always show the truth of demand.

In order to identify regular parts, we like to analyze the consumption time series of the parts to be examined or access the existing ABC and XYZ classifications of the parts in the ERP systems. However, the actual consumption of parts in the past only provides an inadequate picture of Kanban suitability. The usually unavoidable batch sizes in production mean that even very regularly consumed finished parts result in increasingly irregular requirements and thus consumption from one replenishment stage to the next. In the XYZ classification, components whose ultimate sources of demand flow very regularly can therefore also have Z or even Z2 characteristics.

It is a more clever approach to break down the consumption of the finished articles via the BOM structures without taking into account the production lot sizes and to consolidate them from MRP level to MRP level. The resulting XYZ characteristic is a more reliable assessment for Kanban suitability. As previously stated, the following applies: X and Y parts are suitable for Kanban.

Best Practice Module 3:

Kanban suitability is assessed based on the fluctuation in demand for the end products and not on the current fluctuation in consumption of the individual parts.

Basic principle 4: Consistent consumption is not necessarily frequent consumption

Although you should evaluate Kanban suitability without taking production lot sizes into account, you will have to live with the existing lot sizes in practical operation. And so it can and will happen that you come across parts that are only produced at long intervals, despite a consistent final requirement for finished parts. Regular requirements do not necessarily mean daily or weekly replenishment. The frequency with which parts have to be remanufactured depends on the ratio of demand to production batch size. If the requirements are very low in relation to the size of the production batch, it may be the case that only very few batches need to be produced because each production batch lasts a very long time before it is used up.

Controlling such regular but low-frequency parts via Kanban does not give you any direct advantage; the material continues to flow in batches. However, controlling these parts via Kanban does not put you at a disadvantage. We can therefore state:

Best Practice Module 4: The decisive factor for Kanban suitability is the uniformity of demand, not the production frequency of a part. Large production batches in relation to the demand quantity per time unit do not speak against a kanban system; they only reduce the advantage of a kanban mechanism compared to conventional production control methods.

Basic principle 5: The world of demand continues to turn

New parts are introduced into production, old parts are discontinued and technical changes are made to live parts as part of the day-to-day operations of any company. In most cases, new parts are not yet in demand and discontinued parts are no longer in regular demand. Parts in both life cycle phases do not belong in a kanban system.

Leaking parts in a Kanban system were once living parts. If the demand for these discontinued parts decreases continuously and the kanban control cycles are regularly resized, such production parts can only be discontinued in the kanban system if the collective kanban sizes (=production batches) are very small.

However, incoming production parts should only be converted to Kanban when they no longer show a growth trend.

Due to the system, a kanban control cycle always lags slightly behind the change in demand for a part. If the demand for a part increases continuously, the growing demand must be met via the safety stock. If demand falls continuously, the scantling dimensioning will reduce the current stocks with a slight delay. When demand increases, supply availability suffers; when demand decreases, overstocks occur.

In a well-maintained kanban system, all production parts are therefore continuously monitored for their kanban suitability. Parts that are no longer suitable for Kanban are removed and parts that are suitable for Kanban are included.

Best Practice Module 5: Kanban is Bundesliga: all parts that are suitable for kanban play a part here: Parts that no longer belong are dropped and parts that qualify are added. Top Kanban performers carry out this review on a quarterly basis.

Basic principle 6: Technical changes disrupt pull mechanisms.

In practice, there are not only parts that are slowly being phased out because demand is continuously and comfortably declining. Many production parts are taken out of production abruptly without demand having fallen continuously beforehand. This is always the case when a finished product is typically removed from the range by the sales department and its demand or the demand for specific production parts thus ceases. An abrupt discontinuation of demand also occurs when a technical change to a part is introduced into production at a fixed point in time.

In order to avoid residual stocks of the “old” material as far as possible in such cases, superfluous kanban types must be removed from the kanban control cycle in question and, if necessary, the “old” material must be removed. a residual quantity below the yellow area must be produced. This is only possible through manual intervention and targeted communication with production. In such cases, the pull mechanism of the kanban system is de facto overridden by a manual push mechanism. It therefore makes no sense to control parts with frequent technical changes via a Kanban process. Not even if the requirements are otherwise very regular.

Technical changes to parts that do not have to be incorporated into production on a specified date, but rather flexibly after the remaining quantity of the old version of the part has been used up, are not critical. If it is possible to switch flexibly from a predecessor part to its successor part, a successor part can be integrated into the Kanban process without great effort.

Best practice module 6: Successful Kanban manufacturers take care not to use Kanban to control production parts that are subject to frequent technical changes with fixed change dates.

Basic principle 7: Too much of something is poison

When designing a kanban system, you will quickly come up against the question of how many work steps a control loop should cover. There are companies that respond to this with a very simple strategy by turning each production step into a separate Kanban control loop.

If you have the same idea, here’s the good news first: the Kanban mechanism will work and ensure replenishment across all stages of production.the bad news: you should expand your production area quickly so that you have enough space for all the Kanban supermarkets near the respective consumers. The result of this strategy leads to a large warehouse with isolated and hidden production steps between the shelves.

The spans of the existing production orders are a good starting point for the initial definition of the span of the individual kanban control cycles. If production orders have very extensive routings at some points in production and very short ones at others, there is usually a reason for this. In our experience, it makes sense to base the initial design of the kanban control cycles on the existing production orders for the various parts.

When subsequently fine-tuning the control loop spans, it may prove useful to deviate from the existing structures of the production orders at one point or another. It can therefore make sense to combine identical production steps of different parts into one control loop and to form a further control loop from each of the other separate production steps.

Furthermore, there should be no splitting of variants in a kanban control cycle, unless it is a case of clear production in pairs (e.g. left side / right side) or joint production with stable output ratios. However, these are criteria that have usually already been taken into account when defining the work plans and therefore the spans of conventional production orders.

A kanban control cycle should not extend over several production bottlenecks. However, it is of little concern if there are other work steps before or after the bottleneck that do not have a capacity problem and over which the production batches glide without any problems.

However, if you do it cleverly, you can serve several customers (= several supermarkets) in a Kanban control cycle. Each customer then receives their own cards, which are collected by the supplier to form a production batch.

The more Kanban control loops are connected in series in a production process, the more work in progress has to be built up and the more slowly the entire system reacts to changes in demand. You can imagine the mechanism as being similar to that of a queue of cars in front of traffic lights. Long after the first car in the queue has set off, the last one starts to move and long after the first car is already at the next traffic light, the last car in the queue continues to move.

To summarize:

Best practice building block 7: A professional kanban system does not set more control loops in succession than are absolutely necessary.

Basic principle 8: There is no escaping the laws of logistics

Most Kanban textbooks take the easy way out when it comes to calculating the circulating stock in a Kanban control cycle: The average consumption during the replenishment period is divided by the container size, the result is multiplied by a safety factor and “1” is added to it. In the case of a collective kanban, the collective kanban size must replace the “1” (which is sometimes ignored). The safety factor in this calculation model is intended to ensure that any irregularities in demand are absorbed. If you design your kanban control cycles in this way, you probably also set your safety stocks in materials planning using a thumb factor. However, safety stocks are subject to complex statistical laws and must be calculated accurately based on the required statistical readiness to deliver. What applies to classic safety stocks in conventional production control also applies to the calculation of Kanban control loops. More on this later. For the time being, it should be noted:

Best practice module 8: Professionally dimensioned Kanban control loops are specifically designed for a certain readiness to deliver.

Basic principle 9: If you don’t assess the future, you can’t prepare for it

Another impractical theorem that is occasionally heard in the context of lean management is that demand forecasts are no longer needed in a kanban system; after all, the system works according to the pull principle and forecasts are only an issue in push production. Unfortunately, this theorem is only half right: it is true that forecasts are only a matter of push production. However, since kanban systems are not pure pull systems, but a mixture of push and pull mechanisms, you will not be able to avoid demand forecasts if you want to set up a production kanban system that works economically.

A genuine pull mechanism only exists in the case of purely order-related production with a logistical decoupling point outside your own production and procurement. Only if you only react with procurement and production once the customer has placed an order with you do you have to make any assumptions about the future. Whenever you “prophylactically” set aside stock at certain points in the production chain in order to be able to deliver immediately, you need to think about what requirements you are likely to face. And this is exactly what you do with every Kanban control cycle you set up. The dimensioning of each kanban control cycle is based on forecasts of the expected development of demand and its fluctuations.

At best, you can do without forecasts when designing kanban control cycles if you hopelessly oversize the kanban control cycles and thus make them uneconomical. This is why we consider this to be a particularly important best-practice component:

Best practice module 9: A kanban system geared towards delivery readiness and minimum stock requires a good (statistical) sales forecast.

This concludes part 1 of the best practice article on the production kanban.

[1 ] In Douglas Adams’ well-known novel “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy”, the computer Deep Thought answers the question about life, the universe and everything with the number 42.