Scheduling and production control are the heart of the company: They virtually pump the entire value and material flow through the company and the supply chain. But in many companies there is so little understanding of this central task that they are constantly suffering from cardiovascular problems – without even realizing it. With this issue of Potentials, we are launching a new section: “Best Practice Bits”. Using clear basic principles and easy-to-implement best-practice modules, this is intended to provide you with practical tips on how you can optimize your supply chain step by step and get your “logistics cycle” back on track. The first practical potentials deal with the topic of scheduling planning and control and explain how they must position themselves logistically with regard to their readiness to deliver, their stocks and the batch sizes used in order to achieve particularly efficient scheduling.

Can you briefly summarize the tasks involved in scheduling? How about the question: “When do I have to order which material so that it is available in the required quantity at the required time?” The task of scheduling can be broken down to this brief question. What can be summarized so briefly can’t be complicated, can it? Scheduling is also not complicated if you understand the interrelationships and design the scheduling mechanisms correctly, but a look at the practical side shows a completely different picture: scheduling is a frequent cause of annoyance in the company – an annoyance that seems to be part of everyday working life. Regular attempts to improve the scheduling processes are only temporarily successful at best. But it doesn’t have to be that way if you consider the following basic principles and best-practice building blocks of scheduling that can help forge a competitive advantage from a nuisance.

Basic principle 1: Scheduling is the heart of the company, but is often seen by top management as working in a coal bunker.

If top management is interpreted as the head of the company, then scheduling represents the heart. Scheduling pumps the entire flow of goods through the company and the supply chain. In some cases, decisions with a far greater financial scope are made in the planning department than in the case of some management or Management Board decisions, for which the approval of co-directors or supervisory boards must be obtained. Every manager knows that he has to take care of the performance of his heart if he doesn’t want to fall by the wayside at some point. In the same way, the top management of a company must understand at least some basic principles of scheduling so that the economic health of the company does not suffer. This leads to a first best-practice building block, which may be harshly formulated, but can be clearly understood:

Best practice building block 1: Top management should either familiarize themselves with the basic principles and basic laws of scheduling or stay out of the operational business . Why this requirement is so important becomes clearer when we look at basic principle 2.

Basic principle 2: Without clear logistical objectives, no sensible planning is possible.

Don’t you also have the feeling that logistics in general and scheduling in particular are constantly being “rushed around”? We have just discovered that our stocks feel too high and everyone has to take care of reducing them, then customers start complaining about poor delivery reliability and all focus shifts to delivering the products on time. The happy deadline chasing has not even really begun when the production manager notices that capacity utilization in production is at rock bottom and warns everyone to make sure that plant utilization increases again. In the meantime, the purchasing department has found a new, much cheaper source of supply, which, however, can only deliver in larger quantities – and stocks are rising again…

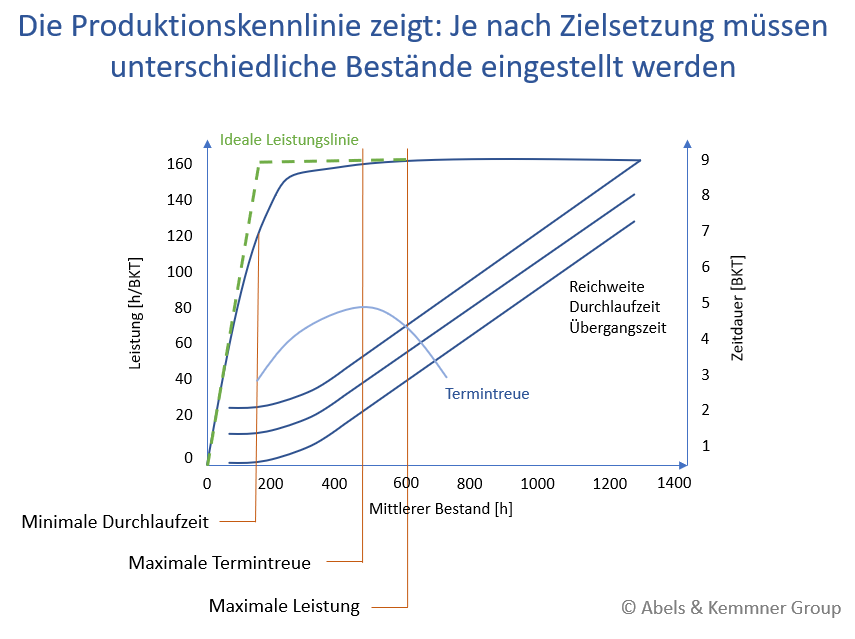

Many cooks spoil the broth – or so you might think. In our experience, however, it is not so much the many cooks as the lack of a recipe to “stir together” the logistics. Improving delivery readiness, increasing adherence to delivery dates, reducing inventories, making better use of capacities and reducing throughput times – unfortunately, none of these things work together. Given the architecture of the value chain and the order situation, there is a clear statistical relationship between inventories, capacity utilization, throughput time and adherence to delivery dates, which can be determined in the form of a production or operating characteristic curve.

Depending on your business and competitive constraints, you must position yourself on this characteristic curve. Logistical positioning inevitably means that you cannot please everyone in the company and in the market and that you have to step on the toes of both the stakeholders in the company and in the market. You don’t want to leave it to your dispatchers alone to decide how hard to step on whose toes? Positioning the value chain correctly in terms of logistics and encouraging the scheduling department to maintain this positioning; this is where the experience and quality of the top management excels! Either you position yourself logistically or you will continue to “wander around” – there is no in-between. Best practice building block 2 is therefore simple and clear:

Best practice module 2: Correct scheduling starts with clear logistical positioning

First of all, we need to take a closer look at a very important logistical target variable: delivery readiness. This refers to the ability to deliver a required quantity of products, articles or components to internal or external customers on the required or agreed date.

Almost all companies have an idea of how high the readiness to deliver should be, without there having to be a consensus between different departments such as sales, logistics and production. The extent to which the targeted delivery readiness has an impact on the required inventories remains just as obscured in the fog of logistical uncertainty as the actual delivery readiness ultimately achieved, which only surprisingly few companies are able to measure at all inventory levels. However, logistical fog stands in the way of efficient scheduling. Therefore:

Basic principle 3: Readiness to deliver is not a variable that arises by chance at the end of a scheduling process, but a target value that the entire scheduling process must be geared towards achieving.

The required delivery readiness on the market is a key strategic parameter for planning and managing the entire supply chain. The various corporate divisions often like to define the key figures in such a way that they can best showcase themselves. We don’t want to argue about the “right” definition at this point; there may well be different truths depending on a company’s boundary conditions and its market situation. However, it is unacceptable that a generally valid definition of delivery readiness is required for all areas in a company and that a clear item-specific (!) specification of the delivery readiness to be aimed for must be set by management.

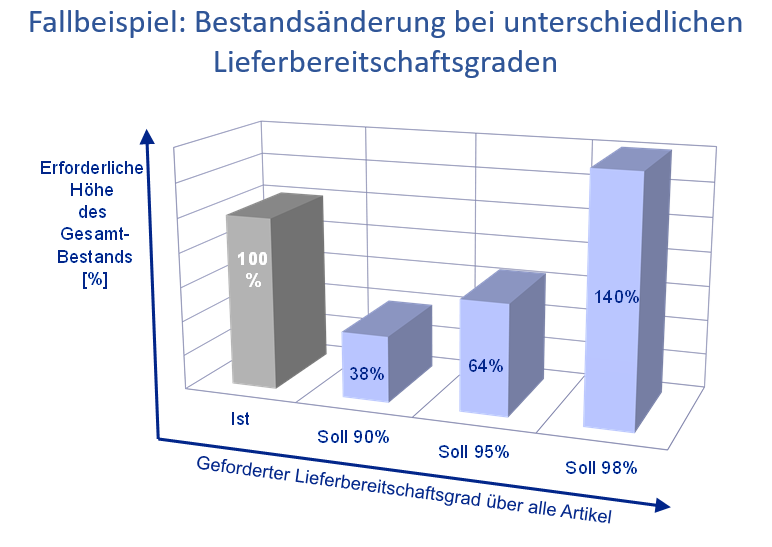

If the correlation between the desired readiness to deliver and the required inventory could be determined using the on-board resources usually available in the company, the “right” readiness to deliver would be more intensively debated.

Especially for items with irregular demand, inventories explode the higher the readiness to deliver to the customer. Items with regular demand, on the other hand, react less sensitively to high levels of readiness for delivery, and experience shows that the same readiness for delivery is often not required at every warehouse level and not for every material and every item. Today, planning simulation systems can be used to precisely calculate which delivery readiness leads to which stock levels for which items. In this way, you can determine exactly what your delivery readiness will cost you and whether you can and want to afford this or what you need to invest in inventory and therefore money in order to remain competitive.

Best practice module 3: In an efficient replenishment system, the required readiness for delivery is defined on an item-specific basis and is checked regularly.

Specifying the target delivery readiness without measuring the actual delivery readiness achieved later is a pure “shoot-and-forget strategy”. You will only achieve a control mechanism if you create instruments with which you can determine and track the actual delivery readiness achieved at all warehouse levels on an item-related basis. Unfortunately, this is the case in most companies:

Basic principle 4: Most companies do not know their delivery readiness and systematically overestimate it.

All the problems and uncertainties in the entire procurement, production and distribution chain are ultimately expressed in two key performance indicators: the inventory in the entire supply chain and the delivery readiness achieved. The required readiness to deliver is the decisive strategic parameter determined by the market and the competition. Inventory, on the other hand, is ultimately a consequence of the efficiency of the entire supply chain and the profitability of the value chain. Even if every company likes to reduce its inventories, the inventory remains a consequence of the supply chain and not a requirement for the supply chain.

The decisive competitive strategy parameter for the supply chain is delivery readiness. And only by comparing the required delivery readiness with the achieved delivery readiness is it possible to intervene to regulate the process. reacting first to the internal or external customer who is best known to the Management Board or who shouts the loudest is not a regulation, but it is the daily business and management philosophy in many companies:

Best practice module 4: Only the systematic measurement of delivery readiness and delivery reliability can turn a second-rate “shoot-and-forget control system” into a first-class supply chain control system.

The reason why the required delivery readiness has such a serious impact on the stocks of some items is due to the required safety stocks for items with uncertain demand, which leads us to Basic Principle 5:

Basic principle 5: Uncertain demand requires inventories or costs delivery readiness

If you don’t know what your requirements will be, but still want to be able to deliver, then you need to prepare for the unexpected by creating sufficient safety stock. The more the internal or external demand for an item fluctuates without a systematic mechanism, such as seasonality, behind it, the higher the safety stock levels must be for the same required delivery readiness. This is one of the main reasons why sales forecasting is so important in the company (see: Best practice rules for sales forecasting). Uncertainties that you cannot eliminate with a sales forecast must be covered by safety stocks. There is no way around this, even if many companies are constantly trying to do so by demanding high delivery readiness and low inventories at the same time:

Best practice module 5: Try to eliminate forecast uncertainties. The remaining uncertainty on the demand side can practically only be cushioned by safety stocks, whether you like it or not.

You should not overlook one important starting point for achieving low safety stocks despite fluctuating demand: How high the required safety stocks need to be depends on the replenishment time, i.e. the time you need to replenish your stocks. The shorter the replenishment times, the lower the required safety stocks can be. At least when it comes to in-house production, a short lead time can only be achieved with lower average capacity utilization. Which brings us back to the logistical positioning. Alternatively, you can change the architecture of the value chain, for example by combining operations and thus reducing transition times. As promising as shortening replenishment times may be, reliable replenishment times are even more important than short ones, as Basic Principle 6 points out:

Basic principle 6: Unreliable replenishment times make scheduling almost impossible to control

How do you generally react to unreliable replenishment times from suppliers or fluctuating production lead times in your production? If you want to be sure that the required material is actually available at the end of the replenishment lead time, you must assume the worst-case scenario of the longest replenishment lead time in your ERP system – or statistically cushion the fluctuation in replenishment lead times according to the required procurement reliability. The second option is more efficient, but is probably not supported by your ERP system. Both variants ultimately mean that you build up safety times and thus safety stocks – now on the warehouse access side. This is because every early delivery leads to additional stocks.

For the reasons explained above, you should avoid uncertainties regarding delivery times wherever possible. On the procurement side, a disturbance variable analysis and clever integration of suppliers into the scheduling mechanisms can be used for this purpose. In the case of in-house production, the first step is to make delays measurable at component level and then to proceed according to the “deadlines are fixed, capacities are variable” system. More on this in a later article, which will deal with the supplementary best-practice modules for production control.

Best practice module 6: Try to improve your suppliers’ adherence to delivery dates. You can only compensate for a lack of delivery reliability on the stock receipt side by using safety times or safety stocks. In a professional scheduling system, this is done by determining safety times based on procurement security.

Unfortunately, short and stable replenishment times are still not enough to achieve best practice scheduling. You must also observe the following basic principle:

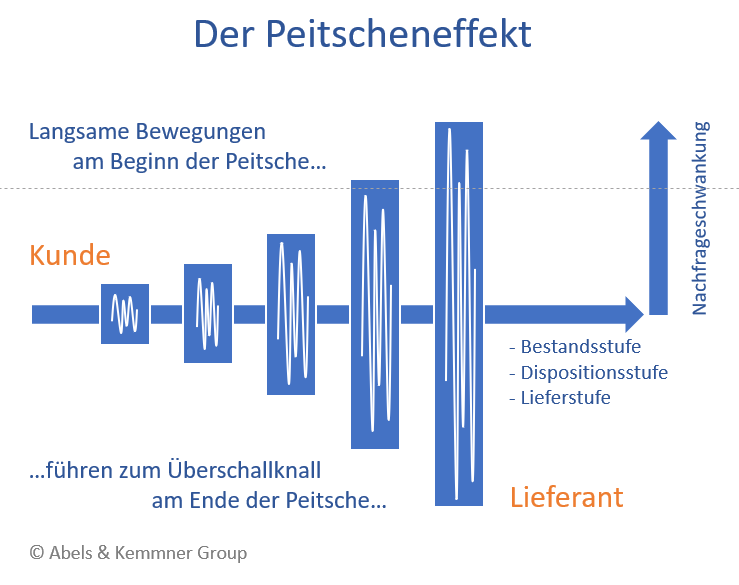

Basic principle 7: A sudden change in replenishment times leads to a sudden change in demand.

Do you know the easiest way to get your customers to bring forward their requirements and send you more orders at short notice? Let them know that your delivery times will be temporarily extended by two weeks (for whatever reason). If the organization works for your customers, then their dispatchers will enter the extended replenishment lead time in the ERP system (unless they switch to an alternative supplier – the concept has a “small” flaw here). During the next ERP system scheduling run, the requirements for two further weeks suddenly become due and a day later you have a two-week requirement for additional customer orders or call-offs on the table. If you are like most companies, you are not at all prepared for this wave of demand on the procurement side, and your ERP system quickly reorders raw materials and purchased parts. You can imagine what happens next: a surge in demand sweeps through the supply chain and drains the warehouses from one planning level to the next.

If you later remove the two-week extension of the replenishment lead time in one fell swoop, the reverse mechanism occurs and the backlog of demand leads to a wave of excess stock that moves through the supply chain, but that’s not all: the consumption and order history of the affected items will show greater fluctuations in the future, which can lead to safety stock levels being increased in the supply chain.

If you later remove the two-week extension of the replenishment lead time in one fell swoop, the reverse mechanism occurs and the backlog of demand leads to a wave of excess stock that moves through the supply chain, but that’s not all: the consumption and order history of the affected items will show greater fluctuations in the future, which can lead to safety stock levels being increased in the supply chain.

As you can see, even intermittent changes to replenishment or delivery times can lead to a logistical earthquake! Instead of making sudden changes to replenishment or delivery times at longer intervals, it is important to regularly communicate even minor changes to your own customers. You should demand the same from your own suppliers and at the same time continuously measure the change in delivery times of your suppliers.

In practice, however, things often look different: In supplier integration projects, we repeatedly find that replenishment lead times have not been maintained for months and sometimes years. The easiest way for us to shorten delivery times is therefore often to simply ask the supplier if they can deliver at shorter notice. So let’s hold on:

Best practice module 7: Changes to replenishment times must be checked and updated regularly and at short notice, and delivery times must be communicated to customers regularly and at short notice. This avoids the whip effects in the supply chain described above. A set of tools with which you can continuously monitor changes in replenishment and delivery times is essential for best practice scheduling.

Once you have replenishment times under control, you need to turn your attention to another basic parameter of logistics, the batch size. Please note here:

Basic principle 8: Batch sizes set for individual materials in isolation jeopardize adherence to delivery dates, delivery readiness and low inventories.

Why do you work with batch sizes in scheduling? Typically because batch size “1” sounds chic and trendy, but is often not feasible for various reasons. You will only be able to order or manufacture a few products in batch size “1” because this is too expensive. Larger batch sizes in procurement often enable the purchasing department to negotiate more favorable unit prices and reduce freight costs. Larger batches in production reduce the frequency of inconvenient and sometimes expensive set-up.

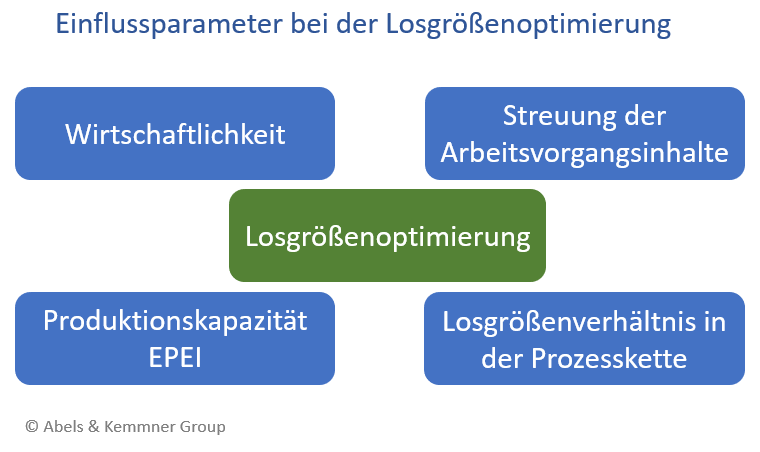

If you question fixed minimum and rounding lot sizes, you often realize that most lot sizes, especially in production, are determined more by gut feeling than by objective criteria. However, the definition of batch sizes has a profound impact on the sensitive scheduling system between parts and storage levels. Correctly set batch sizes can save a lot of money, incorrectly set ones can destroy a lot of money. Five factors play a decisive role in batch size optimization:

- economic efficiency,

- the technology,

- the capacity,

- the spread of order times and

- the quantity synchronization of the production stages.

How many of these criteria do you take into account when determining batch sizes?

In some cases, lot sizes or lot size increments are due to technical reasons. If eight parts are produced simultaneously in an injection mold, it is sometimes technically difficult to use only four nests in the production process. A process such as barrel electroplating is more problematic because it is usually associated with larger batches. If your process is set to a batch size of 3000 parts, you cannot run this process with a significantly different number of parts without compromising quality.

If you produce several parts with one production capacity and reduce the batch sizes for each of these parts, the number of set-up operations may increase to such an extent that the available system capacity is not sufficient for set-up and production. By optimizing the setup, you can solve the problem to a certain extent. At some point, however, setup optimization becomes so expensive that it no longer makes sense.

The limited capacity, the necessary set-up effort and the required production time result in precisely calculable production batch sizes that cannot be undercut. A smaller batch size might be desirable, but is not feasible for capacity reasons. If your product is structured in several BOM stages, then you usually also produce in several successive production stages. The batch sizes at the individual production stages should be in an integer ratio to each other, unless they vary synchronously from order to order. This further restricts you in the definition of batch sizes.

After these de facto batch size requirements and restrictions, there is little room left, at least in production, for one of the supposedly most important batch size criteria: profitability. When determining economic batch sizes, the resulting inventory costs are compared with ordering and set-up costs. By grouping larger requirement quantities, sometimes from the distant future, into a production or procurement lot, you can allocate the necessary procurement costs or set-up costs to many parts so that the costs per part are lower.

On the other hand, you have to keep the parts in stock for a long time, which increases warehousing costs. The usual methods used by companies to calculate economic batch sizes struggle with numerous shortcomings. The cost variables included in the analysis are often inaccurate, the profitability calculation does not take capacity limits into account and ignores the interaction of batch sizes at the various scheduling levels. It is almost irrelevant that all popular methods for calculating economic lot sizes are purely approximate methods, some of which are far removed from the true economic lot sizes.

Last but not least, the working hour contents of different production orders that are run using the same production capacity should be as equal as possible so that you can achieve high capacity utilization with low work in progress and therefore short throughput times. This requirement also ultimately translates into batch sizes, and these considerations should make it clear:

Best practice module 8: Efficient replenishment cannot do without lot size optimization, but requires systematic lot size management and not isolated command actions.

Especially when it comes to batch sizes, it becomes clear how uncritically and without a sufficiently deep understanding of the interrelationships, many companies and users not only mess around with batch size determination, but also with the entire scheduling process. Your interest in these comments already shows that this statement does not apply to you. However, the best-practice building blocks listed so far are just the beginning on the road to an optimally configured supply chain. In the next issue of Potentials, we will focus on the topic of inventory management and the question of how to optimize your basic and safety stocks.