By Götz-Andreas Kemmner

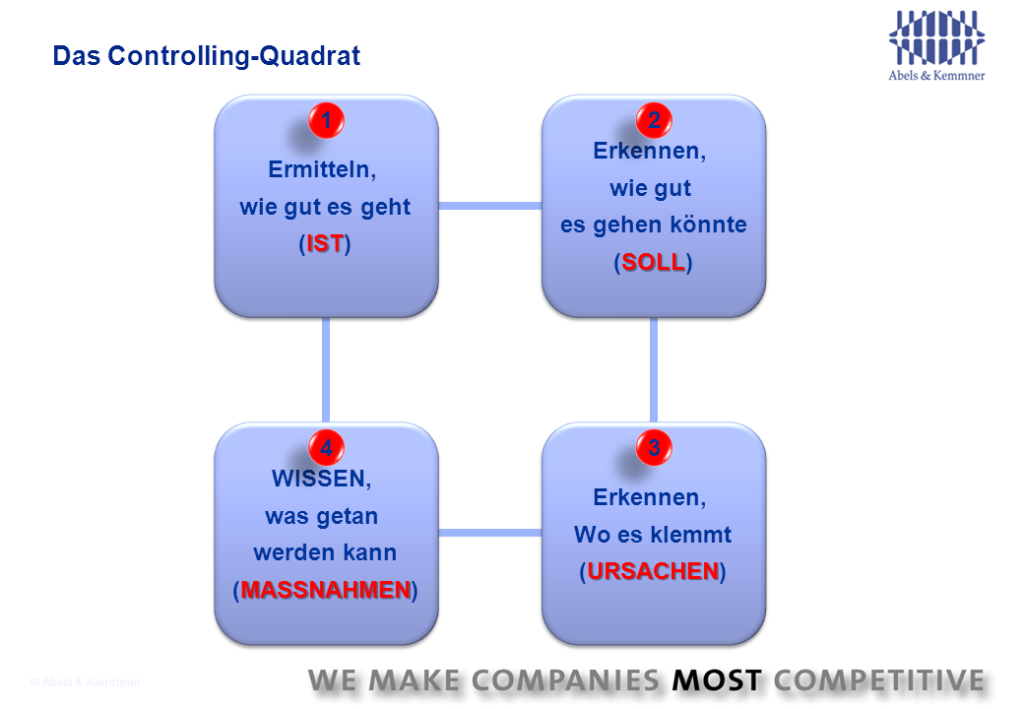

In our projects and training courses on logistics controlling, the expectations are often clear: What are the most important logistics KPIs and what is the easiest way to access them? I then compile these key figures on a monthly basis and send them up one floor, and my logistics controlling is complete…Such logistics controlling does not help with the factual necessity to continuously improve in order not to lose out in the cross-company competition of logistics performance! The exciting and challenging path to effective logistics controlling consists of ten building blocks, which we will present to you in the next issues of POTENZIALE. As always, the journey begins with the first step: Basic principle 1: If you don’t know what you want, you don’t know what to measure. If you want to improve your logistics processes, then you won’t just randomly record any key figures. You will probably first identify weak points, develop ideas for improvement and implement them step by step. Only when you want to measure where you stand and how quickly the work is progressing do key figures come into play. Sounds logical, but why don’t many companies do the same with their controlling? In best-practice companies, logistics controlling is closely aligned with the logistics strategy: The fields of action are defined and broken down based on the logistics strategy. Even if no special measures are required in one area, the (hopefully clear) logistics strategy will result in targets that are then operationalized and made measurable in the form of KPIs. The best practice building block 1 of logistics controlling is therefore: Logistics controlling begins with a clear idea of your own logistics strategy. Even if the strategy is clear, we have not yet arrived directly at the key figures, because… Basic principle 2: Logistics controlling is first about improvements and then about key figures. The English term controlling is often translated into German as Steuerung, but actually means regulation. Accordingly, efficient logistics controlling combines problem analysis with problem solving and thus leads to an improvement control loop based on the logistics strategy. In this context, we speak of the controlling square:

Basic principle 3: You only see potential for logistical improvement if you understand something about it. You only see what you know, Goethe aptly observed, and this insight still applies today. If you want to successfully master the above controlling square, you need to understand something about logistics: Potential can only be identified if you can compare the current situation with a better state. This quickly requires extensive logistical knowledge. Such comprehensive knowledge is also required in order to operationalize and evaluate targets and target achievement using key figures. Of course, going through the controlling square also requires commercial knowledge: An important part of the key figures used in logistics controlling consists of cost variables and financial figures – the profession of the classic controller. Unfortunately, logistics expertise and financial expertise are in different minds in most companies. In the cooperation between the two fields of expertise, a “no man’s land” often opens up between business administration and technology, across which there is sometimes a lack of understanding. This results in key figures that the logistician does not understand sufficiently and those where the businessman has incorrectly translated the technical and organizational issues into financial figures. The key figures in question usually appear serious. The problems with this only become apparent when you delve into the details of its definition. Let’s take the example of logistics costs in relation to turnover or logistics costs per logistics employee. Both key figures are initially crisp. But which cost types from which cost centers are behind this and how can I influence these costs? Are the logistics employees clean? Does this only mean the employees in the warehouse, does it also include production control and scheduling? Does the accrual of employees match the accrual of logistics costs? In best-practice companies, successful logistics controlling is almost always based on logistics management and is supported by cost accounting expertise. This does not exclude the possibility that certain key figures for logistics controlling can and must be specified “from above” or by a central body. Centralized controlling, possibly spanning several locations, will always have to provide specific key figures. However, it is important to be aware that the comparability of key figures in such an overarching controlling system is limited. So let’s take best practice building block 3: Successful logistics controlling drives the logistics improvement process forward and does not just play the role of number cruncher for futile efforts to achieve logistical improvements. Since the key figures alone do not make for good logistics controlling, but must be defined very precisely, the requirements must also be analyzed accordingly. In the next issue of POTENZIALE, we will look at what knowledge is required for this and which targets you should aim for with your key figures. Further information on this topic can be found here: