It’s all about the right planning mix!

From Armin Klüttgen

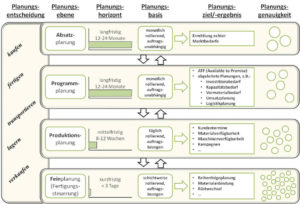

Supply chain management means constantly making a large number of planning decisions regarding the core tasks of “buying”, “producing”, “transporting”, “storing” and “selling”. These decisions are made within the framework of hierarchical planning at different levels, which differ considerably in the scope of consideration and their level of detail. The integration of the different planning levels and their processes is a decisive factor for the quality of planning.

The basic structure of hierarchical planning distinguishes between the following planning types:

- Sales planning (also demand planning, market demand planning, sales planning),

- Program planning (also production planning, operational planning, master planning),

- production planning and

- Detailed planning (also scheduling, sequencing).

The two planning stages, which are at the two ends of the scale in terms of planning time and level of detail, are not included in the following considerations, but are mentioned for the sake of completeness:

A company’s strategic planning is the roughest and most long-term planning level. It is the responsibility of the company’s management and determines the company’s long-term goals, which are to be achieved through strategic decisions. These strategic decisions include, in particular, all those that define which markets are to be served with which products.

The finest and most short-term level is the immediate implementation level. This is where, for example, decisions on machine control and system operation are made and measured values are recorded (PDA: production data acquisition), which can be used to adapt process models in production and for other controlling purposes. This level also includes the “real-time decisions” that are made, for example, as part of order approval, workshop and transport management or customer order management. The integration of the different planning levels, i.e. the question of which level supplies which other level with which information and how this is processed further, is decisive for planning quality. The flow of information runs in both directions, both down the planning hierarchy, i.e. from rough to fine, and vice versa.

Sales planning

The aim of sales planning is to generate an unrestricted market requirements plan (“real market requirements”) on the basis of total market requirements using a coordinated forecasting process. It is important to note the term “unrestricted”. The question to be answered is what quantity of a product or product group the market is likely to be able or willing to absorb. Under no circumstances should the consideration of one’s own possibilities / feasibility, e.g. with regard to machine capacity or personnel requirements, play a role – the forecast therefore takes place against completely infinite capacity. How to deal with market demand planning that significantly exceeds or perhaps even falls short of the company’s own possibilities is decided in one of the subsequent planning steps. Under no circumstances should the sales department incorporate capacity aspects or production restrictions into its sales planning, as this would deprive it of economic potential from the outset and prevent it from considering possible options.

The dimensions covered by sales planning are structured according to product, market and time dimensions:

- Product dimension sales and marketing):

- All products,

- Product groups,

- Product segments and

- Products.

- Markets:

- World,

- Country,

- Market,

- Key Account and

- Customer.

- Time dimension:

- Year,

- quarter,

- month,

- week and

- Day.

From these three dimensions, sales planning now attempts to make a planning statement for certain data nodes. A data node is represented by the respective characteristics of the aforementioned dimensions. For example, a data node would be: A forecast for the product groups 4711 and 0815 in the European countries Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands on a monthly time basis.

The forecast itself is unrestricted and integrated or represents an integrated forecast that generally consists of the best possible combination of a wide variety of information. This combines the technical and statistical forecast based on past consumption, sales information (e.g. on ramp-ups, run-outs, promotions, new / lost customers, regional market changes, etc.) and information from customers.

Sales planning does not consider orders, so it is order-independent in its planning basis. The planning horizon, i.e. the time for which plans are made for the future, is long-term. It covers 12 to 24 months and planning should be carried out on a rolling basis, e.g. monthly, for the corresponding planning horizon.

Program planning

The unrestricted market requirements plan from sales planning represents the input for program planning. The main objective is to create a plan that optimally balances the production possibilities and the forecast market demand. Program planning is also carried out on a rolling monthly basis over a 12- to 24-month horizon. No orders are known in program planning, the planning item is usually located at an aggregated level, e.g. planning in tonnage of a certain type of glass, but not planning of a single glass tube specified in all material properties. In order to be able to assess the capacity effects of unrestricted market demand planning, only the important core aggregates are considered.

Decisions to be made can be summarized as follows: What, when and how much must be produced, taking into account customer agreements, capacity and material restrictions as well as inventory and capacity utilization principles? All relevant restrictions must be taken into account, e.g. business rules regarding customer hierarchies (priorities), market restrictions such as minimum servicing of contract quantities, technical restrictions such as campaigns or transportation restrictions. The key output of this planning is supply recommendations for purchasing, production and distribution as well as ATP statements. At a later stage of integrated planning, these form the basis, based on quotas and contingents, for making an ATP statement to the customer (ATP = Available To Promise: production plan + stock – backlog – confirmed orders = ATP per calendar week and capacity). The ATP term used here differs from the term CTP (Capable To Promise) at the next lower planning level, production planning. In practice, the term ATP is often used in the sense of CTP or other mix-ups. Both together are used as part of the order confirmation and ATP/CTP management in order to make reliable statements to the customer regarding the order quantity and deadline.

In addition, program planning provides important information for a series of derived plans. These include, for example:

- Capacity requirements planning,

- Investment planning,

- Personnel and shift planning,

- External capacity planning,

- Logistics planning,

- Energy planning,

- Maintenance planning,

- Raw materials planning,

- Supply and operating materials planning and

- Sales planning.

As part of program planning, the market requirements are compared with the finite capacities and logistics requirements etc. and thus checked for feasibility. If it turns out that the existing possibilities are not sufficient to meet the unlimited market requirements, decisions must be made on how to deal with this situation, e.g. investing in additional machines and hiring additional staff or assigning defined order quantities to contract workers so that the forecast market requirements can be met. Or you realize that you cannot or do not want to fully meet market requirements because the investment costs would be too high.

The result of these considerations is a company-wide coordinated and communicated limited sales plan, which is then made available to the sales planning level. Only then can sales planning be prepared as another key derived planning parameter.

In reality, the planning steps are often twisted at this point. Sales/budget planning takes place without any form of upstream market demand planning. These are often targets such as “the turnover of the last financial year plus 7.5 %”. These specifications often have little to do with the actual conditions of the products, markets and requirements and result in a permanent entanglement in deviation analyses and a great need to explain why targets have not been achieved.

Production planning

If you try to describe the range of tasks involved in production planning, you are soon faced with the question: What is the difference between this and detailed planning? We will therefore outline the main differences below.

These two planning levels differ greatly in the length of their planning horizon and the level of detail of their planning statements.

Production planning looks at a horizon of 8 – 12 weeks or even more, while detailed planning often only looks 2 – 3 days ahead. With regard to the level of detail, these differences are particularly evident in some industries, namely wherever production is process-driven, where specific batches or even pieces of an item are planned within an order, and not just any number or quantity of an item. The following examples are therefore based in the metal industry (steel, copper, aluminum) and are well suited to describing the differences between the two planning levels. The same also applies to the paper, glass, chemical and many other industries.

In production planning, you coordinate available capacities and materials on the time axis. You fill “time pots” (day, week) with jobs (orders, planned orders) and plan in utilization of the available capacity per time pot. Often, only the key (bottleneck) resources are taken into account.

Detailed planning generates plans down to – in extreme cases – the individual piece or batch of an order. It generates detailed sequences of the production orders and the pieces/batches contained therein for each order. For example, the individual hot-rolled strips, which are cold-rolled next, are scheduled in their sequence in relation to the piece for coiling the cold roll, flanked by set-up processes, which are also placed precisely between certain pieces. Often only one critical resource is planned, e.g. the hot roll in a rolling mill. In detailed planning, all restrictions that determine the sequence of production are also applied in detail.

One example of this is the coffin criterion in the rolling process. This means that during hot rolling, for example, the rolls are first rolled from narrow to wide for a short time and then from wide to narrow for a long time, because the rolls wear from the outside to the inside. These and similar restrictions lead to an exact order and piece sequence in detailed planning, which is not yet planned in this way in production planning.

The aim of production planning is to generate the best feasible plan based on a given mix of orders. Which plan is the best depends on the respective scheduling strategies resulting from the company’s target hierarchy, e.g. maximize delivery readiness, minimize WIP (work in process), minimize inventory, minimize lead time, increase throughput, …

Two stages are often carried out, one planning against unlimited capacity and one against limited or adjusted capacity.

Planning against unlimited capacity enables the planner to identify problems at an early stage and take corrective action. Problems of this kind include late material or late orders, undersupplied orders, capacity or data problems. Against limited capacity, on the other hand, planning generates a balanced plan based on the defined business rules in the form of scheduling strategies. The aim is to eliminate resource overloads without jeopardizing delivery readiness and/or violating material restrictions. Changes to deadlines (start times of work processes) are communicated both upstream and downstream.

The relevant input data for planning are

- Order data (customer and warehouse orders),

- Material information (stock, WIP, orders),

- Information of the factory model (resources, calendar),

- Product data (parts lists, work plans / routings) and

- further model functionalities (setup matrices, campaigns, …).

According to the scheduling strategies, all orders are then scheduled on the time axis using the above-mentioned input data. Usually, the latest possible date is scheduled backwards first. This is stock-optimized scheduling (build up stock as late as possible). Forward scheduling starts from the date on which the primary material is available. This is the earliest possible start date and increases the readiness for delivery, but also the inventory, because it is built up earlier.

Best-practice production planning is characterized by the following features:

- Visibility (transparency)

- Complete visibility (transparency) upstream and downstream.

- Dynamic adjustment of throughput times and planned orders at product level.

- Warnings / reactions to changes (orders or plans)

- Full warning capability,

- Bi-directional transfer of facts throughout the supply chain,

- Decision support tools are an essential part of the planning process.

- If changes in demand or supply occur, an analysis of the effects is carried out immediately.

- Order confirmation

- Complete visibility of the order and customer throughout the process,

- The planning and detailed planning departments have a clear differentiation option with regard to customer orders and forecast orders and have the option of providing proof of origin of requirements for customer orders.

- Planning cycle

- Visibility of all orders, warnings and delivery dates,

- Ability to quickly generate plans and perform “what-if” analysis,

- Complete integration between planning, production and procurement,

- Few people carry out the planning.

- Planning and optimization techniques

- Production planning is systematically optimized on the basis of planning conditions including material, supplier delivery times, customer contracts, etc.

- Integration with other planning systems

- Requirements planning, medium-term planning, production planning and logistics work in a closed loop with shared data usage.

Detailed planning

In detailed planning, the solution approaches are divided into two basic philosophies: deterministic detailed planning and stochastic production flow control.

Deterministic detailed planning is intended to generate a detailed sequence of production orders and operations, if necessary down to the individual piece of a material. This sequence is intended to maximize the efficiency of resources. The resulting production plan is based on detailed rules / specifications and production conditions. As a rule, this planning level takes 2 – 3 days.

The system-supported automated creation of detailed schedules can be very complex, depending on the industry, as the production restrictions that influence the production sequence can be very diverse. The following examples of production sequences and order changes illustrate this:

- Order sequence due to dependencies in the product mix,

- Sequence due to certain production requirements, e.g.

- Painting: from light to dark,

- Hot rolling steel: from wide to narrow,

- produce the best quality first,

- Homogenization in the continuous annealer: gently decreasing / increasing temperature curves,

- Pouring: from lead-free to leaded,

- Dependencies in the tool combination, e.g. in glass production,

- Restrictions due to physical properties such as size, weight, …,

- and much more.

The number of determining factors in the sequence formation can be very large and the interdependencies of these factors can be very diverse. Companies often shy away from the effort involved in system modeling or question the planning result due to the complexity of this topic. Deterministic detailed planning not only struggles with the multitude of influencing variables, which can never be fully captured, but also with their dynamic changes. These two factors mean that detailed plans are often out of date by the time they are completed.

If deterministic detailed planning is to be supported by a system in such a way that good and feasible plans are created automatically, two things in particular must be taken into account:

Firstly, the rules for sequencing, which are stored in the system, should be as lean as possible. The key influencing factors need to be determined and their interaction defined. It should not be forgotten that a large part of the rules already exist anyway, namely in the minds of the planners. This knowledge must therefore be collected, structured and stored in the system.

The second point concerns the way in which system-supported detailed planning is introduced. During implementation, the planning steps that generate the detailed plan should be carried out quasi-automatically. The planner initiates each planning step manually and can observe the result of his actions. This serves to verify the stored rules and creates the necessary confidence in the planning results for the user at the time when the detailed plan is generated fully automatically and thus the necessary acceptance of the system.

Production flow control is based on the knowledge that production is a process that cannot be planned in detail, in which capacity utilization, adherence to delivery dates, throughput time and work in progress are only statistically related to each other.

The task of stochastic production flow control is to keep a defined circulating stock as constant as possible, especially at bottleneck workstations, by means of suitable short-term control of the order inflow or the available capacity. While it is rarely possible to regulate the inflow of orders, production companies with discrete manufacturing usually have the option of a certain degree of capacity flexibility.

Certain restrictions, such as setup sequences or a product mix, can also be taken into account in stochastic production flow control. Keywords here are Heijunka boards, sequencers and EPEI values. Numerous studies and projects have shown that a stable production control situation is achieved in the medium term if the FIFO rule (first in, first out) is consistently adhered to as the overriding priority criterion for individual production orders. Stochastic production flow control is significantly less complex than deterministic detailed planning.

Production control

Production control creates the deterministic detailed plans and is responsible for stochastic production flow control. It also supports and optimizes production execution with information that enables all production activities to be optimized, from order release to the finished material. It can also cover a variety of key functions in addition to production scheduling and execution, such as data collection and recording, quality management, process management, material flow management, production tracking, document control and personnel management.

Order confirmation (ATP / CTP management)

The order confirmation process combines the findings from program and production planning to provide customers with the best possible information about their order quantities and deadlines. Program planning provides information on the ATP by checking how much of the planned quantities in the respective pots (buckets, quotas, quotas) are still free or already allocated (AATP = Allocated Available to Promise). ATP is allocated at a specific “level” within a defined sales hierarchy, which should be aligned with the sales planning hierarchy. In some cases, allocation is based on rules that assign quantities to the respective ATP pots, e.g. “fair share based on the requirements plan”, “fixed split” or “based on customer priorities”. Redistribution between the ATP pots (ATP exchange) also occurs frequently in practice. The ATP check enables the customer to receive reliable confirmation of a desired delivery, and quickly.

So that the program planning statement, which already takes place at a coarser level, has the highest possible quality, so-called netting takes place between the program and production planning levels. Here, the orders currently planned in production planning are offset against the situation in program planning according to defined rules, so that program planning, which only takes place monthly, can provide an updated ATP statement to the order confirmation process at any time.

Production planning, on the other hand, confirms in the form of the CTP check that an order with its specific quantities and deadlines is feasible in terms of capacity and the availability of primary materials. This process can be used as confirmation (at production planning level) that the delivery week (based on ATP) is feasible.

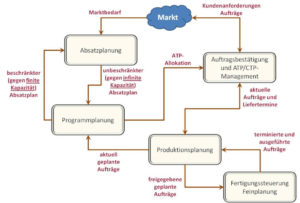

Integration of the planning levels

The way in which the different planning levels are integrated is decisive for the quality of the plan. In practice, it is not uncommon for production planning to act completely independently and more or less ignore sales planning. The reason for this is often that the results of sales planning are simply unsuitable for the purposes of production planning, e.g. if they represent pure budget planning that has nothing to do with real “market demand planning”. In such a case, there is a hard cut between sales planning and the underlying planning levels. Coordination between the levels only takes place again during the order confirmation process, when Sales requests the desired delivery readiness and Production Planning has to explain why the required quantity is not available on time for a specific customer order.

In a basic planning run that is consistent across the levels of the planning hierarchy, information must be communicated in both directions of the hierarchy.

Sales planning transfers the market requirements plan against infinite capacity to program planning. Based on this information, this in turn carries out a capacity analysis at a rough level against limited capacity, which then influences various derived plans in the next step, e.g. personnel or sales planning. The results of this planning step are made available to the sales department as a plan.

Program planning also supports the order confirmation process by enabling quantities and deadlines to be confirmed at a rough level (ATP). In order to be able to do this reliably, the currently planned orders from production planning are netted with the ATP situation in program planning.

For its part, production planning qualifies the order confirmation process by providing the delivery dates for the current orders, taking precise account of the input material and capacity (CTP). The orders are received via sales order management and fed into production planning.

Detailed planning receives the released planned orders from production planning, which are then precisely scheduled for a very short-term horizon and implemented by production control. The information on which orders have been scheduled or executed and how is transferred back to production planning, thus closing the planning loop.

These basic functionalities described here at the interfaces between the planning levels are used in practice in a variety of individual ways.

Conclusion on hierarchical planning

The form of hierarchical planning described above is not always found in its entirety. There are often variants or subsystems of this planning.

Variants are expressed by the fact that the individual planning levels are designed differently in terms of their tasks or are used differently in terms of their timeframe and/or their level of detail. Variants also occur insofar as their interaction is defined differently at the interfaces between the planning levels.

Subsystems do not cover all of the planning levels described above; program planning in particular exists only rudimentarily or not at all in many companies, depending on the industry. Detailed planning is also not used as consistently in many companies. However, even in these cases you will usually find some kind of Excel sheet, where the detailed planning, carried out manually and very laboriously, has a somewhat shadowy existence.

Complete hierarchical planning is not necessarily a “must” to achieve the greatest possible economic success in some sectors! It is crucial that a company identifies and undertakes the planning effort that is necessary and justifiable in order to be able to achieve the formulated corporate goals with sufficient planning quality.

It is important to design the right planning mix.