What are the 5 basic strategies for the economic optimization of a supply chain? The ideal image of modern production logistics is characterized by the idea of market-synchronous production: producing what the market needs. Ideally not in advance, but just in time. This ideal version of market-synchronized production is hardly economically feasible in any company today – if it ever was.

Customers and markets are far too “impatient” for that. They demand high delivery readiness, want short delivery times and on-time deliveries. The increasing number of variants in product portfolios further exacerbates this problem. In most cases, therefore, only a moderate increase in demand is spread across a broad product portfolio, which reduces demand for the individual product and causes it to fluctuate overall. In practice, we regularly hit our heads against the ceiling when trying to produce this widely distributed and fluctuating demand in line with the market: the capacities in production, the available personnel or the suppliers’ ability to deliver are not sufficient.

Strategy mix against impatience

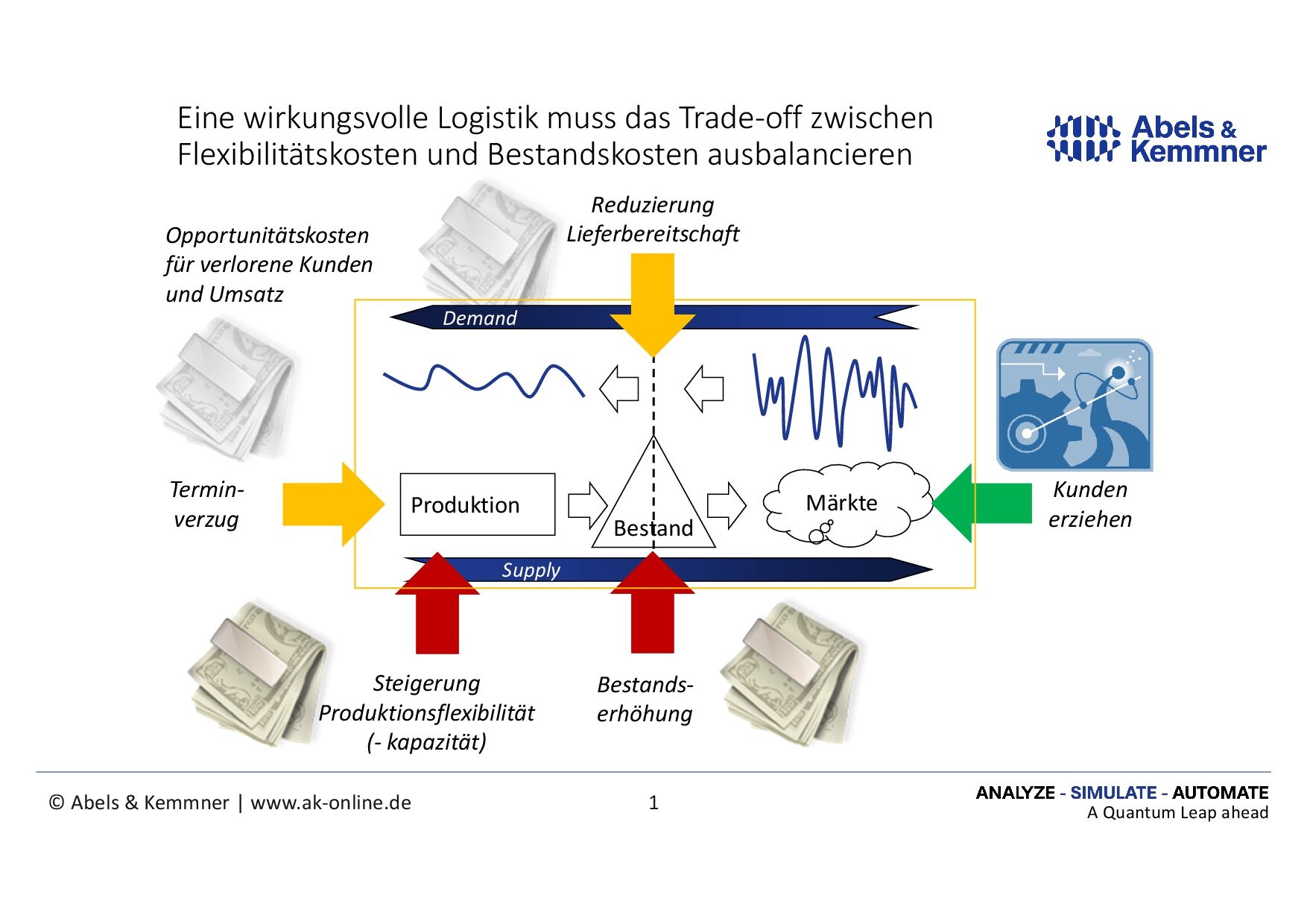

In order to survive economically in such an environment, it is important to find the minimum balance between supply chain flexibilitycosts and inventory costs. Simply put, but only approximate in practice. We can choose between five basic strategies for dealing with flexibility costs and inventory costs. Striking the right balance between these variables is an essential element of a logistics business model:

- Strategy 1: Maximum flexibility We are increasing our production flexibility so that we can meet any market demand. This usually requires us to maintain higher production capacities or, if we are not yet producing around the clock and around the week, to allow personnel capacity to fluctuate. However, this not only costs overtime and special bonuses, but often also requires a generally higher number of staff. The advantage of this strategy is low inventories in the value chain.

- Strategy 2: Maximum inventories Instead of demanding a high degree of flexibility from the value chain, we can also try to seal off production from the market firestorm by building a firewall of inventories. Such a firewall is always possible at the logistical decoupling point – for make-to-stock manufacturers, typically at the finished goods warehouse, for variant manufacturers at the component warehouse before assembly. Although this results in high inventory costs, we save on flexibility costs in production.

Both extremes are so expensive that they are practically never used. Costs can be reduced by compromising on flexibility on the one hand and on inventories on the other, resulting in two pragmatic strategies:

- Strategy 3: Pragmatic inventories A frequently used method is to reduce delivery readiness. As we all know, the required safety stocks virtually explode when delivery readiness levels exceed 95%. Every half percent reduction in delivery readiness can save considerable inventory costs and, of course, increase liquidity.

- Strategy 4: Pragmatic flexibility Just as a reduction in delivery readiness reduces the necessary inventory costs, an accepted delay in delivery reduces the necessary flexibility costs in production.

Of course, these two strategies do not come for free either. At the very least, there is a risk that customers will jump ship and we will lose sales to competitors. Unfortunately, it is rarely possible to calculate exactly how high the opportunity costs for this are. However, anyone with a few years of practical experience knows that these costs do arise.

- Strategy 5: Queue As a last resort, we can try to educate customers to be patient. From a logistics perspective, this is the ideal solution that allows a high degree of forward planning in the supply chain and enables low inventory costs and low flexibility costs. The European automotive industry has been particularly successful with this strategy. This strategy can only be used by actual or perceived monopolists. There are few of the former, but plenty of the latter – who drives the “wrong” brand of car, buys the “wrong” brand of watch or switches from one long-standing and inexpensive supplier to another? If customers absolutely need the products, a de facto monopolist can perhaps expect them to grudgingly wait in the short term, but economics shows us that de facto monopolies do not last long. Perceived monopolies can remain effective for longer, as the automotive industry has shown us over the years, but high marketing costs are incurred and customers are still lost due to excessively long delivery times.

None of the five basic strategiesrepresents a real silver bullet for optimizing the supply chain. The right compromise is crucial for the success of supply chain management.

Using simulation, the solution for optimizing the supply chain is not rocket science

With the dynamic value streams of modern supply chains, it is practically impossible to find the right strategy mix with simple static considerations, such as a classic value stream analysis. It is not enough to concentrate on representative articles, nor are average values sufficient for a differentiated analysis of the situation.

However, finding the right compromises to work as economically as possible is not rocket science. A dynamic simulation based on empirical data can be used to develop a coordinated strategy mix. To do this, extensive data from the ERP system is transferred to a digital twin and thus mapped the value streams including the planning and control model. Such a digital twin not only allows a stress test of the existing logistics business model. It also makes it possible to further optimize the logistics strategy and arrive at a suitable strategy mix.